Graticule

Patrícia Domingues

My practice traces lines between geological phenomena and transatlantic history. As a jewellery artist and a stone cutter, I focus on the properties and qualities of materials but also on their respective histories and the environments we cohabit with them.

The fractures and the cuts I consciously create in materials are performative gestures and intersections of the materials’ stories and my own in the past and the present.

In this paper, while exploring a personal, fragmentary approach towards creative writing and revisiting family lineages, I will use an autoethnographic methodology to divagate between landscapes of union and disunion. I will embark on an interweaving of lines—my own, those of the material and of history—as a way of expanding my practice into a broader scene of ideas and events. From the boats docking in Lisbon during the fifteenth-century Portuguese colonial period, to the exploration of gemstones at German markets and my grandfather’s abandoned notebooks, how do the lines of history translate into a sequence of performative gestures? Where does the past end and the present begin?

Keywords: Lines, Gemstones, Fracturing Practice, Intimate Writing, Landscapes

Editors’ note: This text has both experimental footnotes and scribbles hand-drawn by the author that interact with the text. We’ve tried to adapt them to the web format, but they are better appreciated in the pdf.

1 – Interdependence

In his comparative anthropological study of the line, Tim Ingold looks at things, people and places as the sum of interconnected lines. For him, to study these is to study the lines they are made of, “After all, what is a thing, or indeed a person, if not a tying together of lines – the paths of growth and movement – of all the many constituents gathered there?”[1].

Amongst the particularities of lines that most fascinate me is their capacity to mimic each other and their interdependence. A fault in the land, before it becomes a fault, is a network of smaller fractures. The event of one fracture will stimulate the next and they continue to form until finally they succeed in cracking a massive amount of rock. This phenomenon is often observed when two tectonic plates separate from each other. The hot mantle then rises from the depths of the Earth and occupies the space created by the fault, like blood flowing from a cut in the arm, that solidifies to form a scab. Thus, lines are made of continual gestures, but also of intervals and discontinuities. In these gaps the influx forms new land, and new lines are created where life can then proceed. Through these encounters, fresh magma is pressed against much older rocks and later on exposed to the surface by erosion. As a result, when we look at the ground, what we see is the coming together of different times, a multiplicity of events, enriched and characterised by layers.

Lines that bend or break, that slither and wriggle and come into existence by internal and external accidents, permeate their environment and grow into unexpected places. Hence, lines that entangle are conceivably difficult to classify: Their beginnings and ends, if they exist at all, are blurred, hard to grab and materialise. For that reason, it is important to look closer, to devote more attention, because after all, what is life and research if not a tangle of lines?

2 - A brittle crack

A typical brittle crack grows in three stages. During its “birth” from an initiating notch, it accelerates in less than a millionth of a second to reach a speed almost equal to the speed of sound. During “childhood” the crack continues to accelerate, but more slowly. All this time the crack is straight and the fractured surfaces in its wake are smooth and mirror-like, but once the crack speed rises above a certain threshold, a mid-life crisis sets in: the velocity starts to fluctuate wildly and unpredictably, and the crack tip veers from side to side. Then the fracture surfaces become rough, sprouting a forest of small side branches. A fracture is never linear, the growth is self-amplifying and the effect does not follow in proportion to the cause. A tiny crack can turn into a catastrophic one.[2]

3 - Line and blob

The idea of individuals as lines entangled in their environments and intertwining is rather different to what has been accounted for in ecology and sociology, explains Ingold:

In those fields, people and organisms are seen as blobs. Blobs have insides and outsides, divided at their surfaces. They can expand and contract, encroach and retrench. They take up space or—in the elaborate language of some philosophers—they enact a principle of territorialisation. They may bump into another, aggregate together, even meld into larger blobs rather like drops of oil spilled on the surface of water. What blobs cannot do, however, is cling to one another, not at least without losing their particularity in the intimacy of their embrace. For when they meld internally, their surfaces always dissolve in the formation of the new exterior.[3]

Confronted with the realisation that like lines, blobs form part of our world, Ingold’s intention within his dedicated research on lines is not to reject a blob view of the world but rather to complement it. According to him, any form of social life that does not lead to an interlacing of lines cannot exist. While blobs give volume and mass, lines give movement and connection, constituting the matter from which life is made.

“What lines have, which blobs do not, is torsion, flexion and vivacity. They give us life. Life began when lines began to emerge and to escape the monopoly of blobs. Where the blob attests to the principle of territorialisation, the line bears out the contrary principle of deterritorialisation.”[4]

4 – De tajar

In Spanish: Tajo - De tajar[5]

(divided in parts, cut).

1. A cut, usually deep and smooth, made with a knife or other cutting instrument.

2. A deep, vertical cut formed in the ground by erosion, e.g., by a river, or by some other natural event.

The Tagus[6] is the longest river on the Iberian Peninsula. It crosses the central part of Spain and, following an east-west direction, ends up dividing Portugal in two, ending its journey by draining into the Atlantic. It is an historical river loaded with departures and arrivals, and the intersections of boats, people and goods have dramatically and permanently changed the course of the modern era. I have often watched its waters flow into the Atlantic; in certain places, it is possible to see how the two waters pacifically blend into each other. The meeting of the fresh and salt waters sometimes manifests as a delicate line marked by distinct colours that change depending on the weather: grey-blue with a soft beige—the variations are perhaps endless. But most of the time, this line is in fact colourless, almost imperceptible, the kind of line that turns invisible when one isn’t paying attention but, nevertheless, does not cease to exist. It is a line of expansion, a kind of controlled rhythmic and constant release. I imagine such continual movement to be different from the energetic spurt of a volcano or the squish of a tectonic fault. Those geographies of fire only release energy at certain times. Whereas the river is in constant renewal.

Only a few kilometres out from the Tagus estuary the waters of the Atlantic become troubled, in comparison with those of the Tagus that descend from Spain in a rippling and sensuous movement. While the former erodes the land unobtrusively, the latter brutally dislodges land from the coast. I was in my twenties when I first heard the meaning of the word Tajo (‘Tagus’ in Spanish). Before then I had never thought of the river as a cut in the land excavated by the water. Learning the sharpness of its name irrevocably changed my relationship to it.

Ever since then, I like to think the river brought me its meaning from a foreign land.

5 – Gift

In 2011, I received a gift from a friend. An agate stone which, despite its ordinary appearance, contains a special phenomenon. The lines in the centre indicate that while in the ground, the stone had been broken into two pieces and naturally glued back together with the help of other minerals (probably silicon dioxide and carbonate) that penetrated it, closing it up again.

I imagine it is most likely dazzling on the inside, as agates usually are. Within, they are often partially hollow. Most start with strong concentric lines, from the outside to the centre, that are interspersed between layers of quartz and silica, creating lines of different colours. These lines normally end with small crystal formations that are followed by an empty nucleus. But this particular stone might be different. Its weight makes me wonder whether it actually is hollow, or perhaps solid inside. The absence of sound when I swing the stone with my hands leads me to believe that there are no crystals inside. It makes me think that it is made up only of hard and dense materials.

A – Agatha stone, image by the author

6 - Physical and imaginary lines

I am an immigrant, and travelling, especially within the European Union, has been a constant part of my life. And although mostly restricted to this continent, my trips around Europe have been extensive enough to involve traversing several different kinds of borders, bringing me to question the kind of lines I was crossing and dealing with. Those forming the perimeters of countries are invisible most of the time, forced into existence. They are not physical realities, and yet they have such a strong impact on people’s lives. I feasted my eyes on the natural, twisting ones, following the rivers and mountains that I encountered on the way, and on the direct lines of the highways that allowed me to cross all the imaginary and physical lines in only a few days. I became very interested in the relationship between human beings and their territory, in how land and cultures could be fragmented and how this fragmentation could be directly reflected in the landscape. Themes around the individual and the collective concerned me, as well as those of the cultures of different countries. In other words, I became interested in the need that human beings always have todivide territory up, creating spaces, real or imaginary, where one’s culture-identity can be developed, at a distance from others.

7 - An account book

My grandfather worked as an accountant for a metal-casting company in Lisbon. He had thousands of account books that he would fill with numbers. He died before I was born, in a car accident on one of those asphalt lines that criss-cross entire landscapes and cities, and often interrupt people’s lives. So unfortunately we never met. However, I still have some of those books, some completely filled with his beautiful handwritten numbers, others that have remained empty. I can't say that the smell of antiquity that emanates from the books once you open them is pleasant, but it doesn’t bother me.

What I particularly enjoy is drawing in the unused books, breaking through the gridlines that fill every page. It is satisfying to observe an organic line, full of imperfections and faults, developing within such a rigid structure.

One day, while we were having lunch in one of our favourite restaurants in Lisbon’s Graça neighbourhood, my father told me that my grandfather’s company cast several pieces of the train lines that were later built in Africa. He simply spoke the words; we looked at each other and were silent. I think we were both reflecting, in that moment, on the weight of such a fact. I knew my father’s political ideas well enough to imagine what he might have been thinking.

My grandfather, like my father after him and like every Portuguese citizen, directly or indirectly, was connected to lines of occupation in Africa. But in this specific case, my grandfather was indirectly connected to what Ingold refers to as the transport lines or connector lines. The kind of lines that changed our perception of the environment, and the ways in which we relate to it, probably forever:

The line, in the course of its history, has been gradually shorn of the movement that gave rise to it. Once the trace of a continuous gesture, the line has been fragmented—under the sway of modernity—into a succession of points or dots. This fragmentation, as I shall explain, has taken place in the related fields of travel, where wayfaring is replaced by destination-oriented transport, mapping, where the drawn sketch is replaced by the route-plan, and textuality, where storytelling is replaced by the pre-composed plot. It has also transformed our understanding of place: once a knot tied from multiple and interlaced strands of movement and growth, it now figures as a node in a static network of connectors. To an ever-increasing extent, people in modern metropolitan societies find themselves in environments built as assemblies of connected elements. Yet in practice they continue to thread their own ways through these environments, tracing paths as they go. I suggest that to understand how people do not just occupy but inhabit the environments in which they dwell, we might do better to revert from the paradigm of the assembly to that of the walk.[7]

I gradually realised that the lines of occupation in Africa were the beginning of a modern transport line, and how colonialism has the shape of a blob which occupies and robs space but doesn’t inhabit and care for it. Unlike the lines of trails that are formed by wandering and wayfaring, through the continuous motion of searching or digressing, the lines of transportation, that connect dot to dot, are built in relation to the incoming and outgoing traffic that is believed to pass through them. The lines we have created to transport the fruits of extraction became deeply instilled in us and inside of us.

8 – Rail line

The imagery of the rail line stretching across the African landscape resonated in me over the years. I would think about it now and then; I suppose I still do. Perhaps that explains the empathy I felt while reading Bruce Chatwin’s Songlines. In this book, the idea of straight lines imposing onto more round and organic lines comes alive. The rigid straightness of the train lines in Australia not only contrasts with the roundness of the paths of the Aboriginal Australians but has also created interruptions in the sacred process of singing to the land along circular and meandering paths. Songlines materialises the idea that alterity is not linear, but for Tim Ingold this is a slightly erroneous concept. He says it is very tempting to describe every linear approach as colonial behaviour, but for him, colonialism is not an imposition of a linearity upon a non-linear world but an imposition of one kind of line on another.[8] The Australian Aborigines affirm that a territory cannot be divided into blocks, but only into a web of lines that interlace with each other, entangling with the textures of the world.[9] While Europeans and our trainlines gradually turned into blobs—imposing cutting lines, to straighten our immediate paths—we are historically bound to the kind of trace we follow and leave behind us, and the existence of lines is undeniable. Instead of debating their existence, we should rather look at the intention of the line.

9 – Fissure

- A long, narrow opening or line of breakage made by cracking or splitting, especially in rock or earth. Split or crack (something) to form a long, narrow opening.

- A state of incompatibility or disagreement.[10]

10 - Celeste

Wayfaring, I believe, is the most fundamental mode by which living beings, both human and non-human, inhabit the earth. By habitation I do not mean taking one’s place in a world that has been prepared in advance for the populations that arrive to reside there. The inhabitant is rather one who participates from within in the very process of the world's continual coming into being and who, in laying a trail of life, contributes to its weave and texture.[11]

One day, talking to elderly relatives back home while on a break from university, I discovered my grandfather had a sort of very tiny atelier in Lisbon. From my Auntie Celeste’s description, I imagined his workshop as a corridor between two buildings, in one of the narrow streets of Lisbon, a city which was then under the authoritarian rule of the “New State” regime (1933–1974). In this studio he began to experiment with using acid to etch metal, a personal interest I assume stemmed from the company where he used to work.

My Auntie Celeste didn’t know exactly what it was that he made there: coins, medals, experiments…these were the words I heard. Years before ever hearing my aunt tentatively describing my grandfather's interest in metals, when I was still in high school, I myself experienced etching copper with ferric chloride, which is a kind of acid. When I heard the stories I instantly connected visually and sensorially to what my Auntie Celeste was saying and could easily imagine my grandfather wrapped up in his experiments. Copper etching is indeed a fantastic technique because, depending on the amount of acid used, you may have more or less control over the intensity and the effect of the erosion on the metal. If you leave the acid on the metal for too long, it will run freely across the surface, corroding the metal and leaving behind a rugged appearance which produces an organic, but also in some sense a harsh, feeling. I occasionally meditated on that and asked myself what kind of feedback my grandfather had got from such experiences, away from the lines of the account book and the lines of the dictatorship. I sometimes hope the lines of the acid touching the metal surfaces were the kind of lines that went for a walk, as Ingold mentions, wayfaring, entwining, and hailing freedom.

11 - Pandemonium

We had a house in Lisbon’s Encarnação neighbourhood that was no longer inhabited after my grandmother passed away. One day the house was broken into and burgled, the burglars having entered through the back door. In fact, it was burgled repeatedly, to the point where the back door broke permanently and could no longer close. As a result of this, cats entered and lived in the house for an indeterminate period of time—it could have been months but also years. One day, after the successive robberies, I visited the house and found a scene of devastation. Dust, furniture, books, papers on the floor, traces of the cats’ presence—absolute chaos as I recall. This is when I found my grandfather’s account books. I picked them up carefully from the floor, one by one. On the same day, I found a framed poster on the floor that used to hang in the office room. It was a very minimalistic image, a black profile of the figure of Fernando Pessoa wearing his hat; an iconic profile, easily recognisable to almost every Portuguese person. The frame was on the floor and I could see a dark stain on its back, probably cat urine, and as I turned the frame over, I could see how the urine had acted like acid and aggressively corroded part of the paper. Some parts had even disintegrated, leaving small fragments of paper which were stuck to the glass. The paper, together with the uric acid, had dried out, as mud does on a warm day, creating a relief full of meticulous details and saliences. Burned by the acid, the stain gained several shades of brown, giving it an earthy-ground appearance, surprisingly not unlike the effect of a metal etching technique. I brought the poster on the frame glass with me because I thought the stain was beautiful. I liked the form left by the urine attacking the paper and the fact that, because of the paper's poor condition, the poster could no longer be detached from the glass. The stain is located at the feet of Pessoa, and it gave me the feeling that now he had ground, a trail where he could walk and wayfare perpetually. It left me amazed that such a vulgar event could create such an impression of beauty.

B – Encarnação, photograph by Hernando Domingues

12 - Navigation tool

I had a second experience of robbery in my life, this one more disturbing than the first. It happened while I was driving from Portugal to Germany. Not far from Madrid, while I stopped my car to take a break and drink a coffee, everything that was inside the car was taken in a matter of minutes, perhaps seconds. This event was particularly disturbing since I was moving permanently to Germany, so I had taken all my personal possessions with me: my books, my clothes, my tools, my drawings, even one of my grandfather’s books that I took great care of. I remember returning to the car and seeing what had just happened. Time seemed to pass more slowly in those first few seconds. The doors and car bonnet were open and lying on the ground. Still fluttering in the winds that swept the arid, sandy ground of Spain was a cartographic map. I had bought it in an antique shop because I was obsessed with maps and because I wanted to see if I could draw lines on the map to generate overlapping lines. I couldn’t, and my experiment failed. I guess it failed because I respected the lines of the map too much. I would just stare at them, not daring to draw on them. The thieves saw it as just a map when they vandalised the car. It was the only thing that survived the robbery. So I lost all my belongings, but I still had a map.

13 - Shops in Idar-Oberstein

Nature and humankind have always had a relationship that ebbs and flows. Our fascination with materials, especially those only available elsewhere, has often led us to struggle, exploit, and destroy. The desire for raw materials rose sharply during colonial times and has only continued to grow. The thrill and awe other people feel for rare materials is something that I observed when I arrived in Germany and entered shops selling precious and semi-precious stones in a very special place called Idar-Oberstein. A town well-known for stoneworking, Idar-Oberstein is replete with ateliers that are still working and exploring this millennium’s stone-carving and faceting techniques. Surrounded by various mines and an unspeakably stunning landscape, Idar-Oberstein is a geological wonder and a place where different times and realities collide, the geological and the human.

Until the eighteenth century, the area was a source of agate and jasper, and the river Nahe provided the perfect conditions for the creation of a European gemstone-working centre; the river provided free hydropower for the cutting and polishing machines at the mills. It was only after the eighteenth century that the gemstone sources in the Hunsrück region started to dwindle. In an attempt to find alternate sources, miners and dealers travelled to Brazil and Africa, discovering, in 1827, the world's most important agate deposit in Brazil's state of Rio Grande do Sul.[12] Around 1834, the first delivery of agate nodules from Rio Grande do Sul was shipped to Idar-Oberstein. Admiring the beauty of the Brazilian agates, which exhibited very even layers, much more even than those seen in the local stones, Idar-Oberstein’s engravers made exquisite figures out of the rare gems.[13] This, combined with local expertise in chemical dyes, helped the industry grow bigger than ever by the turn of the twentieth century. In Idar-Oberstein’s Deutsche Edelsteinmuseum one can find several mementoes of these journeys to Brazil. On the wall of the second room, a Guinness World Record awarded to an Agatha’s druse that has been cut into 75 discs is displayed. Originally the geode was about 1.5 metres across, much bigger than anything the stone cutters of the region had ever seen.

Today, a much broader variety of gemstones can be found in the shops of Idar-Oberstein. Rose quartz from Brazil and Madagascar, Indian jasper, amethysts from Uruguay, quartz from Brazil and Colombia, Bolivian ametrine, moss agate from India, rhyolite from Texas, chalcedony from South Africa, Mexican dalmatian jasper, heliotrope and aventurine from India, tiger’s eye from Australia, malachite from Congo, Chinese turquoise, lapis-lazuli from Afghanistan, Peruvian chrysocolla, rhodochrosite from Argentina, sodalite from Namibia, dumortierite from Mozambique, Sri Lankan sapphires, rubies from Kenya, tanzanite from Tanzania—the list goes on and on.

Stones from all over the world are displayed in vitrines, sometimes even caged, like in natural history museums where nature is exhibited in the form of trophies or semiophores.[14] They are cut in half and polished, revealing a glittering spectacle which bears witness to the geological history of the Earth. Naked, seductive, displayed on the shelves showing their flat surfaces, the stones look like modern computer screens, on show in a computer shop. Their screens are portals to a parallel world of an almost eternal endurance. As I walk along corridors, I reflect on how easy it would be for me to grab one, it would only take a second to have it in my hands. All things are potentially nameable, and they are all potentially “ready-to-hand,” as Heidegger says.[15] The shelves are designed in such a way that every human body feels central to the scenario, from every viewpoint each shelf is like a conveyor belt, full of stone fragments, organised by quality, colour, size, and diversity, all coming within reach of our hands.

C - Deutsche Edelsteinmuseum. Photograph by the author.

D – Cages. Photograph by the author.

14 - Letters to the king

Inevitably, the Portuguese influence of the fourteenth century came to my mind. Letters written to the king,[16]detailing the riches found by explorers in foreign lands, are an incredible testimony to the desire for raw materials and the looting practiced during that period (see Boxer).[17] Gold from Guinea, emeralds from Ethiopia, diamonds from Angola were just a few of the most sought-after materials. Something about the immediacy of those shelves in Germany brought to my mind the way the goods would arrive in Lisbon directly at Praça do Comercio, and how the city centre was structured around them. Once unloaded, each type of product travelled a different route, and the more organic lines of navigation followed on the sea would be substituted by the rigid streets of Lisbon, all the way from downtown to the upper town. It is still possible to find traces of these material structures; Lisbon’s Gold Street and Silver Street are examples. Of course, I have never seen goods being unloaded in Lisbon, just as I have never seen stones being unloaded in Germany. Only traces of the act of extraction remain for me to observe as I look silently at thealien landscape of a common shop in the middle of Germany.

[18] I realised that we resort to that giant surface we call the ground when we want to be free of something, perhaps because the Earth lets us forget. The ground is the not-seeing. It is where we bury our dead, where we hide disturbing or, on the other hand, precious things.

[19] I sometimes bury my hands in the heaps of precious stones in the shops of Idar-Oberstein. It reminds me of the sands of Portugal and I like the sensation on my skin. I try to do it on the sly, but I think the shopkeepers already know me, and they turn a blind eye to my slightly unorthodox attitude. I bury my hands and sometimes my arms too in piles of rubies, diamonds from Pakistan, amethysts and garnets, exercising irresistible pressure, forcing aside any opposition, as a bulldozer would do.

[20] I realize now that the ground is the biggest line of all, the one that subsumes the immaterial with the constructed. The world is a multitude of grounds and atmospheres, because everything is either seen or not seen. And everything is hidden or it is hiding something else. Everything is simultaneously a tridimensional line and a filling, a tube through which the flow passes.

E – Sand. Video by the author.

16 – The Writing of Stones

I cut a gemstone apart and was instantly awed by the beauty I found inside, but the cut seemed almost an act of aggression, as if I were cutting the world. As if I were using the diamond saw to cut a highway in a landscape, or a train line, crossing lands and tearing apart a sort of cosmic matrix made of infinitesimal connections. How could I split apart such an image, imprinted in the gemstone through a complex crystallisation process, irrevocably changing the initial event?

When I read Roger Caillois’s The Writing of Stones, I felt the same as when I heard my Auntie Celeste describing my grandfather’s metal experiments. I could relate, because I too have observed stones and gemstones from inside. Roger Caillois explains that there is an immense world inside a gemstone, a world of exquisite and simultaneously dreamy landscapes. As Marguerite Yourcenar explains in the introduction to The Writing of Stones, Caillois was accused of anthropomorphism because he claimed to have observed a consciousness and sensibility in every corner of the universe.[21] But he claimed instead an inverted anthropomorphism, something that stands for a kind of Copernican revolution, where humans, like every living and non-living organism, are part of the gear that moves the whole. We are no longer the centre, but the centre is latent in every single thing in the universe.

It is possible that, back in the 1960s and 1970s, Roger Caillois read The Cosmic View: The Universe in 40 Jumps, published in 1957 by Kees Boeke. This was a breakout work that later influenced the acclaimed Powers of Ten (1968, re-released 1977) by Charles and Ray Eames. I wonder what their initial thoughts were when those authors saw the first-ever picture of Earth taken from space.[22] Today such images are common, but back then it must have caused a pronounced visual and even ideological shock. We could finally look at our own planet and realise that its own image is not so different from a blue marble that we could comfortably hold in one hand. Conceivably, those must have been exciting times supported by scientific and technological advances. Just as images from space exploration reached us, so images captured by nanotechnology, from inside organisms, proliferated amongst us. In every corner of the universe, on every surface, in every organic and non-organic material, from molecules to stars, a breathtaking and living world exists. Roger Caillois knew that the world is finite – things repeat, combine, and overlap, creating recognisable patterns in diverse environments. Every surface holds the potential to enter into other dimensions, and the world is nothing more than a constant inside and outside repeated at different scales in a fractalised and intimate relationship.

Caillois, in The Writing of Stones, suggested that once a stone is opened, a world of ideas is accessed, displaying incredible similarities between the outside world and the inner world of a gemstone. What was hidden often looks like landscapes, mountains, rivers, skies, stars or sometimes even ruined cities with fantastic heroes. In his research, Caillois was persuaded to think that human invention is only a development of the data inherent in things, including minerals and stones, which hold a form of calligraphy inside.[23] Caillois believed that no matter what image an artist creates, be it abstract or figurative, no matter how absurd it is, there is in the world’s vast natural store an identical image: “No matter what image an artist invents, no matter how distorted, arbitrary, absurd, simple, elaborate, or tortured he has made it or how far in appearance from anything known or probable, who can be sure that somewhere in the world's vast store there is not that image's likeness, its kin or partial parallel?”[24].

F – Cut. image by the author.

17 – Photo album

My father was a photojournalist, and as a consequence our home was full of black and white pictures. Some of the political situation of the time (1961—1990), from the Portuguese Revolution,[25] the Colonial War,[26] portraits of politicians, and some of the Portuguese countryside. Of course, some pictures were of our family too, of simple trips to the beach or trips to other countries and continents. He was devoted to black and white photography but with time, some colour photo albums were also added to our collection. As an only child, it fascinated me to reorganise these same albums by mixing them up. I can’t remember exactly what criteria I used to select pictures and curate new albums but, in the end, every album contained a bit of everything, from the experiences of my family to the collective experiences of society. An album always tells a section of a story, fragments of a fragmented life. But the spectrum of an album can always be amplified or reduced, depending on the focus. As they were amplified, my albums also became more fragmented since they allowed parts of many collective and individual spheres to cohabit.

Currently, my worktable is full of materials: natural stones, (hard and soft) artificial and synthetic materials, metals, non-metalloids, woods, silicon, plastic, shells, fossils, etc. Some were found and I have left them in their original form; some I have manipulated. A collection of fragments that has been brought together over the past 10 years while I have been exploring the landscape of the Hunsrück and the gemstone shops of Idar-Oberstein. My workplace has slowly been transformed into a kind of imitation altar. Natural materials live alongside man-made materials, just like in cabinets of curiosities, where man-made objects were exhibited next to natural finds. I have tried to organise the material landscape by taking an empirical view, studying the materials and their significant differences and similarities in origin, size, shape, substance, quantitative aspects, and even different uses throughout human history. While I study what the landscape is made of, I fragment it, creating sections and rooms. But these rooms are only temporary. Ultimately, by cohabiting the studio-practice space, the materials and I mutually shape each other. In this daily interaction new resonances and new lines are brought to light. In my studio, materials seem to be democratised. Considering them equally valuable, I use them as a means to think about technology, artefacts, landscapes, living and non-living beings diving into a world of correspondence.[27] Through these materials, I gain a glimpse of a more intertwined, less fragmented, world.

G – This table. All images and works by the author.

18 - A line made of people

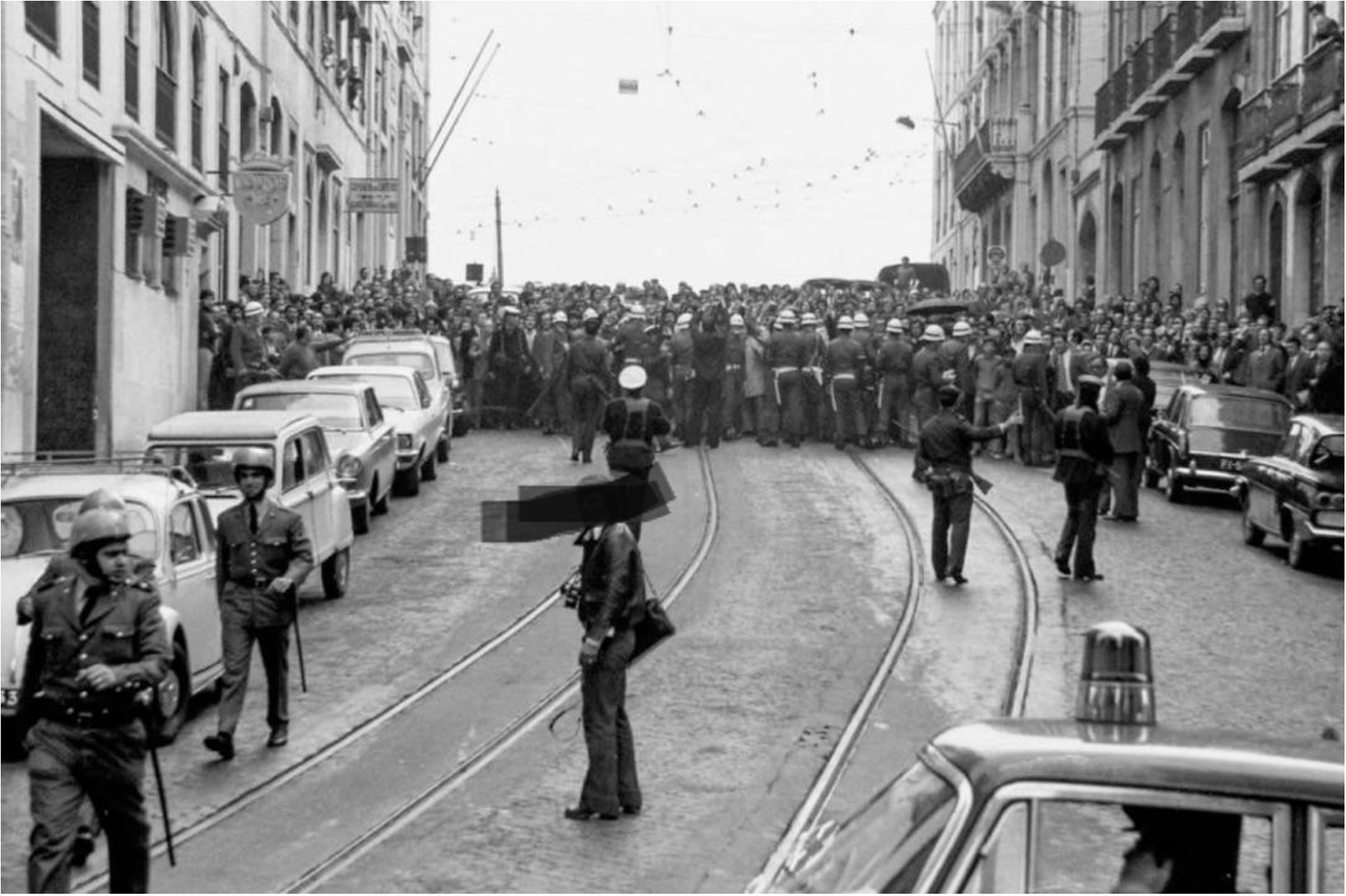

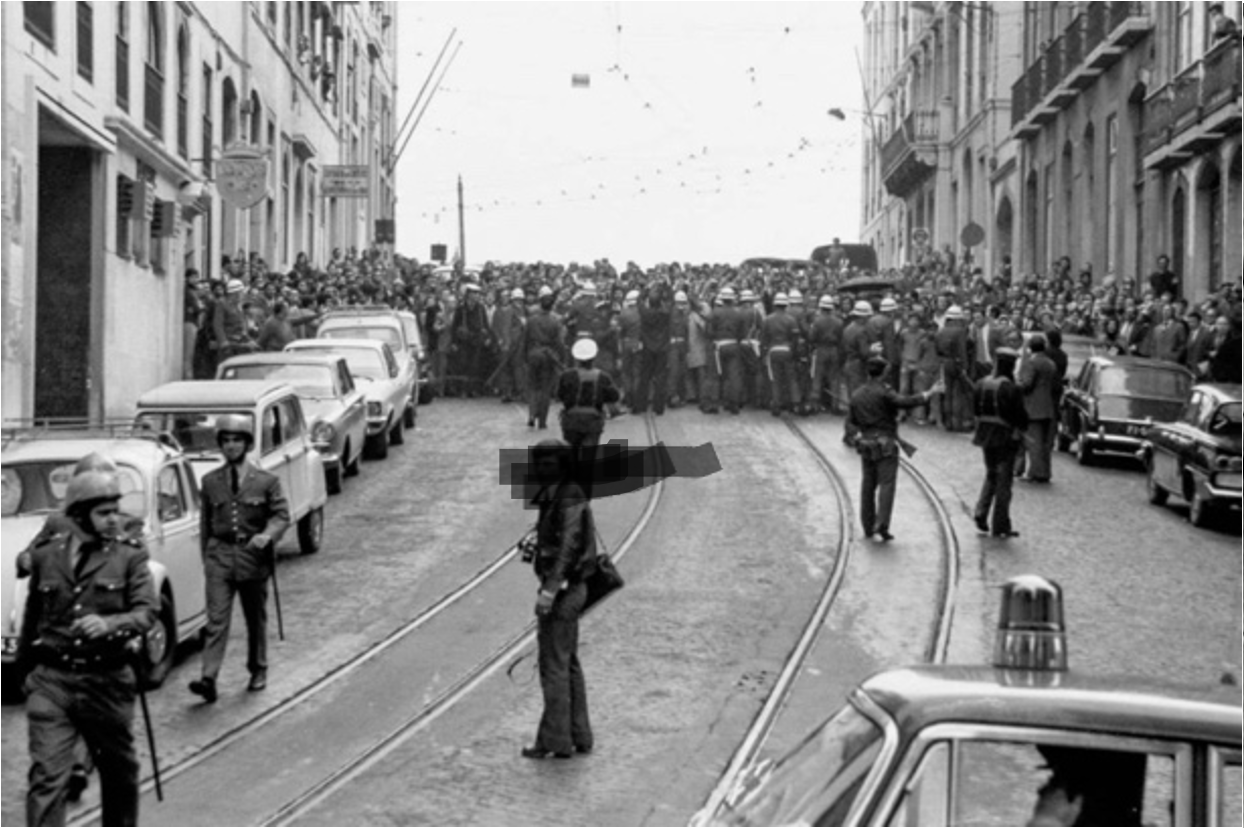

I found this picture (H - Rua Victor Cordon below) a few days after my father passed away in hospital in 2014. A colleague and friend of his had posted it on Facebook with the caption, “Look, Hernando caught in action.” I was surprised because I had spent my whole life looking at pictures taken by him but had rarely seen pictures of him. My mother was right beside me, we both looked at the picture and she immediately recognised a moment to which she had often returned in her mind: 25 April 1974, Victor Cordon Street in Lisbon. The Portuguese army re-established a democratic regime in Portugal, after 40 years of dictatorship. We recognised my father in the middle of the street carrying a camera. She proceeded to tell me that she remembered this moment perfectly, because she too had been there. Not where my father was standing in order to immortalise the moment, but on the other side, in the crowd, together with the other protesters. She told me she had had a headache that day and her boyfriend at the time had called her, telling her “there is a revolution happening out there, might be better to stay at home.” She had ignored his advice and gone out to join the revolution.

Since coming across it I have often admired this picture of my father. There is a quality in the performative gesture of the line formed by the group of people that reminds me of the lines I made in my grandfather's book, the hypothetical lines of acid explored by my grandfather on metal, those of uric acid on paper, and those printed on stone by the geology of time. These lines contained a spontaneous beauty,[28] a sense of oddity and some anomaly that contrasted with the rigidity of our inhabited world.

H - Rua Victor Cordon. Unable to verify authorship by time of publication.

19 - Properties and qualities

Only years later, in 2017, when I began my doctoral research in the arts, did I realise how the process of creating the lines that I drew into my grandfather's ledger (see number 7, An account book) was fundamentally different from the process of mapping the Earth. The former involved me imposing my organic, irregular lines onto the grid already present in the book, while the latter requires the opposite—the superimposition of a grid of latitudinal and longitudinal lines (a graticule) onto the organic lines of the map, in order to be able to project the Earth onto a flat surface. In this way, space can be compartmentalised and thus better defined and measured, and ideally territorialised.[29]

I gradually came to understand that the way we deal with space and time is intrinsically connected to the way we handle materials with our hands. I have come to realise that movement is the very essence of perception: Only because we scan the terrain of events and objects, moving from the close by to the distant can we perceive them. As a jewellery artist, the special way in which I approach materials is not to see them simply as physical realities, nor only as an imagined idea I have of them. Rather, they are stories even before they turn into physical objects. Those stories are of my own engagement with life that leads my research more in some directions than others. But they also include stories of materials before and after my path crossed with theirs. I realise how their concrete nature can never be completely objectified, as in modern concepts of territorialisation. Mapping and scanning the world should ultimately be a process of inclusion and not only of fragmentation. The properties of nature are our own. And yet we subject them to our shifting environmental perceptions.

From an empiricist perspective the properties of a material or an object, such as colour, size, texture, etc., can be externalised and seen to be independent of each other. They are thus fragmented and compartmentalised in order to be organised according to the norms of empiricist research. But from a phenomenological perspective such disruption is ultimately problematic. Imprecise knowledge, by which I mean that which cannot be quantified, such as colour, smell, texture, and even stories, has a value that is worth pursuing despite the difficulty in measuring it.

Thus, the properties and qualities of an object and the way we perceive things unfolding in time and space are phenomenological and sensorial experiences that change and are relational and in which the whole constitutes more than the distinct parts.[30] The lines I make in materials are an inquiry into the matter, meant to transverse their physicality to connect in a broader sense with their surroundings. They are lines that result from embodied activity, lines that inhabit my space and practice. While I cut materials, saw them, break them apart, and bring them together, my gestures carry a sort of muscle memory, tacit knowledge implicit in my patterns of action that is bound up in the lines I make and turn myself into while wayfaring around in a process of care and knowledge.

I – am. Imagined Erosion, 2020. Reconstructed marble, steel. Brooch – (50 – 40 – 10 mm). Image and work by the author.

20 - Nature's existentialist questions

The way cracks form patterns makes me think they are nature's existentialist questions, fractal structures repeating on all scales, running in veins, aggregating, and breaking.

21 – Jewellery box

Often, a jeweller has a close relationship with their mother’s jewellery box, from their childhood. They often describe the feeling accompanying opening a mysterious box which contained simultaneously the smallest and the biggest treasures. I am, of course, no exception. My mother’s was a dark, wooden, pentagon-shaped box with a geometric star pattern on top. It was fascinating to rummage around in it and pull out all the beaded necklaces, huge earrings, fascinating art deco bracelets and some unusual golden rings. My mom isn’t exactly a conventional woman—quite the opposite—and her jewellery was unconventional for the time, but also elegant and assertive, as she herself is.

After trying the pieces of jewellery on, a ritual that could last for several hours, I could never put them back in the same way that I had found them. It always looked like a whirlwind had passed through, and I wasn’t able to close the box properly. There was always a cleft, a crack that revealed my passage. I don't know if I was unable to put things back as they had been or if, in fact, I didn't want to...maybe that little opening in the box was a signature of my presence, a physical manifestation of the fact that I, along with my mother's jewels, had been transformed through that experience. So nothing could be the way it was because things had changed. As with the materials that I currently transform in my studio, this was a process of bodily alignment, a body that is spatially located and does not conquer its space by being territorial, but rather by cohabiting and permeating it.

22 - Los Jardines que se Bifurcan

When I discovered a second picture of that exact moment in the centre of Lisbon on 25 April 1974, I remembered the work of the Venezuelan artist Juan Araujo (1971). Araujo had had an exhibition in Lisbon called “Los Jardines que se Bifurcan” (“The Gardens that Bifurcate” ).[31] The title was stolen from Jorge Luis Borges’s book and related to the labyrinth of references and appropriations that define our creative processes.[32] When I placed both pictures of the Revolution side by side, I noticed how, unbelievably, they were almost identical and simultaneously so dissimilar. It is impossible to say how much time had passed between the two and which was taken first. The second photo was taken by the photojournalist Alfredo Cunha, but the photographer of the first remains unknown. In the first, my father was present; in the second he was gone. Looking at these two pictures was like looking at a gemstone cut through the middle, or at Araujo’s work Mickey and yekciM (2018) (K - The opening of time, below). They seem almost identical, yet minor details differ – shapes, opacity, colours, etc. Thus, the opening is the passing of time, and walking through Araujo's exhibition, where images of different worlds seemed to duplicate while bifurcating, was like opening a book or opening up a stone. It was as if time itself forked, since the cut had duplicated the image.

See H for reference.

Photograph by Alfredo Cunha.

https://www.stephenfriedman.com/usr/documents/press/download_url/16/1573305043_arau_artforum_february2019.pdf

https://www.stephenfriedman.com/news/20-juan-araujo-el-jardin-de-los-senderos-que/

23 - Inherit

Perhaps the power of the objects that we touch lies in the fact that they touch us back. We inherit their stories and their lines; we inherit the landscapes they have witnessed and experienced and the stuff they are made of. And this inheritance is a silent inheritance, which does not knock on the door, but moves along, like a river or a crack in a stone.

[1] Tim Ingold, Lines – A Brief History (London: Routledge, 2016), 5.

[2] Philip Ball, Branches. Just for the Crack (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2009), 77.

[3] Tim Ingold, The Life of Lines (London: Routledge, 2015), 16.

[4] Ingold, The Life of Lines, 17

[5] Definition from Oxford Languages. https://www.google.com/search?q=tajo+significado&client=safari&rls=en&sxsrf=ALeKk00KNfBe_3x94T8_eY7M_wJ09iUoXg:1625736947116&lr=lang_de&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwihgeyJltPxAhWXOuwKHeWbB5sQuAF6BAgBEAE&biw=1255&bih=675

[6] In Spanish Tajo, and in Portuguese –Tejo.

[7] Ingold, Lines, 77.

[8] Ingold, Lines, 3.

[9] Ingold, Lines, 82

[10] Definition from Oxford Languages.https://www.google.com/search?client=safari&rls=en&q=fissure+meaning&ie=UTF-8&oe=UTF-8

[11] Ingold, Lines, 83.

[12] See Wilhelm Lindemann, Will Larson, and Ekkehard Schneider, Dreher Carvings, Five Generations of Gemstone Animals from Idar-Oberstein (Stuttgart Arnoldsch, 2017).

[13] Idar-Oberstein engravers were often specialists in carving animals, and each engraver and stone cutter would become known for one type of animal, for example, wild pigs or birds.

[14] Semiophore—carriers of meaning—is a term introduced by Krzysztof Pomian. Objects turn into semiophores when they are removed from their original context of use and become part of a museum collection. See Magdalena Michalik http://cejsh.icm.edu.pl/cejsh/element/bwmeta1.element.ceon.element-7d8e54fe-488f-3492-8204-00b887541e18/c/pdf-01.3001.0011.7254.pdf

[15] Hartmut Bohme, Fetishism and Culture, A Different Theory of Modernity (Berlin: De Gruyter, 2014), 24.

[16] John I, also called John of Aviz, was King of Portugal from 1385 until his death in 1433. His 48-year reign, the longest of all Portuguese monarchs, saw the beginning of Portugal's overseas expansion.

[17] See Charles Ralph Boxer, The Portuguese Seaborne Empire (Lisbon: Edições 70, 1969).

[21] Marguerite Yourcenar, introduction to The Writing of Stones, by Roger Caillois (Charlottesville, VA: University Press of Virginia, 1985), xi.

[22] On 24 October 1946, rocket scientists captured the first images of Earth taken from space. This is the first photograph of Earth ever taken from space. It was captured 105 km above the ground from a rocket that had been launched from the White Sands Missile Range in New Mexico, USA.

[23] Yourcenar, introduction, xviii.

[24] Roger Caillois, The Writing of Stones (Charlottesville, VA: University Press of Virginia, 1985), 3.

[25] The Carnation Revolution (Portuguese: Revolução dos Cravos) of 1974, also known as the 25 April (Portuguese: 25 de Abril), was initially a military coup in Lisbon in which the authoritarian Estado Novo regime was overthrown.

[26] The Portuguese Colonial War, also known in Portugal as the Overseas War (Guerra do Ultramar), or in the former colonies as the War of Liberation (Guerra de Libertação), was fought between the Portuguese military and the emerging nationalist movements in Portugal's African colonies (Angola, Guinea-Bissau and Mozambique) between 1961 and 1974.

The pictures of the Colonial War (taken by father) were not explicit – there were only a couple of them and they were portraits of my father.

[27] This is a term used by Tim Ingold—Things correspond to each other when they live in a sympathetic union, rather than an assemblage of parts. In correspondence we attend to one another. (Lecture - Training the Senses: Tim Ingold - The knowing body. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=OCCOkQMHTG4).

[28] I am thinking here of Caillois and the way he describes spontaneous beauty: “This spontaneous beauty thus proceeds and goes beyond the actual notion of beauty, of which it is at once the promise and the foundation” (The Writing of Stones, 2).

[29] “It was only consciously formulated as a method in the second century AD by the Greek geographer Ptolemy, who employed a grid of geometrical lines of latitude and longitude (called a graticule) to project the earth onto a flat surface” (Brotton11).

[30] Christopher Tilley refers to the materiality of the stone as a total sensory experience in which the whole is more than the parts (The Materiality of Stone – Explorations in Landscape Phenomenology [Oxford: Berg, 2014]).

[31] Culturgest Fundation Caixa Geral de Depósitos, Lisbon 2018

[32] https://www.culturgest.pt/en/whats-on/juan-araujo/

Acknowledgements

To my dear friend Maria Gil Ulldemolins, to my PhD co-promoter Nadia Sels and to Kris Pint, founders of the journal Passage, an eternal thank you. Working with you has allowed to perceive research in the arts as a intime unfolded map full of complex freedoms. Thank you for having trusted my work for the first edition of Passage. This experience, truly enriched and opened-up my world.

Bibliography

Ball, Philip. Branches. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2009.

Boeke, Kees. Cosmic View: The Universe in 40 Jumps. New York: John Day, 1957.

Bohme, Hartmut. Fetishism and Culture, A Different Theory of Modernity. Berlin: De Gruyter. 2014.

Boxer, Charles Ralph. The Portuguese Seaborne Empire, 1415—1825. 2nd° ed., Lisbon: Edições 70, 1969.

Brotton, Jerry. A History of the World in Twelve Maps. London: Penguin, 2012.

Caillois, Roger. The Writing of Stones. Translated by Barbara Bray. Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1985.

Chatwin, Bruce. The Songlines. New York: Penguin, 1988.

Eames, Charles and Ray Eames. “Powers of Ten.” 1968, 1977. YouTube video. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0fKBhvDjuy0.

Ingold, Tim. The Life of Lines. London: Routledge, 2015.

Ingold, Tim. Lines – A Brief History. London: Routledge, 2016.

Lindemann, Wilhelm, Will Larson, and Ekkehard Schneider. Dreher Carvings, Five Generations of Gemstone Animals from Idar-Oberstein. Stuttgart: Arnoldsch, 2017.

Michalik, Magdalena. The Institution of the Museum, Museum Practice and Exhibits within the Theory of Postcolonialism

Preliminary research. Muzealnictwo 59 (2018): 28–33. doi:10.5604/01.3001.0011.7254.

Tilley, Christopher. The Materiality of Stone - Explorations in Landscape Phenomenology. Oxford: Berg, 2014.

Yourcenar, Margerite. introduction to The Writing of Stones, by Roger Caillois, xi–xviii. Translated by Barbara Bray. Charlottesville, VA: University Press of Virginia, 1985.