Thick Time, Thin Places

I. Threads of Time

Solstice I

I am sitting at the top of the stairs in the house where I grew up (Figure A). I am around ten years old and it is the start of the school holidays, just after the summer solstice. The long evening sunlight stretches inside, hazily illuminating the lace curtains hanging in the window and thickening the air, revealing floating motes of dust. I feel a heightened sense of attunement to my surroundings: the natural environment outside the open window, the tremor of the leaves, and the soft sough of the wind. The neighbours’ garden across the way is verdant, abundant, and shimmering with life. I am suddenly overcome by a presentiment of nostalgia: I sense the fleeting nature of this moment, and realise that one day it might no longer be possible to return to this scene.

The nature of time

Time, “the original shape-shifter,”1 remains one of the most taken-for-granted and least understood features of our lives.2 Omnipresent, it permeates every aspect of human existence, yet it is visible to us only in its traces. Pondering the elusiveness of time, the fourth-century theologian and philosopher Augustine of Hippo confessed, “I know well enough what it is, provided that nobody asks me; but if I am asked what it is and try to explain, I am baffled.”3 More than a millennia and a half later, in his book The Order of Time (2018), theoretical physicist Carlo Rovelli admits “we still don’t know how time actually works. The nature of time is perhaps the greatest remaining mystery. Curious threads connect it to those other great open mysteries: the nature of the mind, the origin of the universe, the fate of black holes, the very functioning of life on Earth.”4

An ambiguous relationship

The anthropologist Edward T. Hall was fascinated by the multifaceted, ambiguous relationship between time and humankind, observing how we variously “speak of it as being saved, spent, wasted, lost, made up, crawling, killed, and running out.”5 This ambiguity is something I can personally relate to – grappling with purely linear concepts of time, I often find myself resisting the strictures of set timetables or deadlines. According to a theory put forward by Hall, this might suggest an understanding of time that is polychronic rather than monochronic.

Hall associated monochronic or M-time – “doing one thing at a time” – with Northern European and North American cultures, and defined it as a conceptualisation of time that is linear and ordered, divisible, rigidly compartmentalised into schedules that are fixed and inflexible. He contrasted this with polychronic or P-time – “doing many things at once” – which he claimed was the typical understanding of time in Mediterranean, Middle Eastern, and Latin American cultures. More fluid and malleable than M-time, “P-time stresses involvement of people and completion of transactions rather than adherence to preset schedules. Appointments are not taken as seriously and, as a consequence, are frequently broken [...] For polychronic people, time is seldom experienced as “wasted,” and is apt to be considered a point rather than a ribbon or a road.”6

Time as lived experience

Hall was keen to point out that rather than being natural or inherent, any conceptualisation of time is “arbitrary and imposed, that is, learned.”7 Sociologist Barbara Adam likewise stresses that how we perceive and conceptualise our experience of time “varies with cultures, historical periods and contexts, with members of societies and with a person’s age, gender, and position in the social structure. The meanings and values attributed to time, in other words, are fundamentally context-dependent.”8 Adam’s research has exposed how dominant Western theories about time are premised on “positivist belief in an uncontaminated, objective reality” and thus fail to recognise the inherent subjectivity of time as experience.9

Architect Jeremy Till shares Adam’s view, arguing that “One’s experience of the world is radically affected by different modalities of time. In this light, time (in all its guises) is apprehended not as an abstraction to be intellectually ordered, but as a phenomenological immediacy to be engaged with at a human and social level.”10 Till uses the term thick time to describe the coexistence of multiple temporal modalities where none predominates over the others. Thick time is multidimensional, an expanded present “that gathers the past and holds the future pregnantly, but not in an easy linear manner.”11

Knots in time

Another architect, Lina Bo Bardi, always maintained that “Linear time is a western invention; time is not linear, it is a marvellous entanglement, where at any moment points can be chosen and solutions invented without beginning or end.”12 Bo Bardi’s reference to “points” correlates with Hall’s explanation of polychronic time, and her idea of time as a tangle brings to mind something I once read describing an indigenous Australian belief that “You can’t pull time apart or separate it.”13 In the Aboriginal Australian concept of the Dreaming, there is no distinction between past, present, and future. Cultural theorist and philosopher Erin Manning writes that “the Dreamings are like knots where the actual meets the virtual in a cycle of continuous regeneration […] these knots of experience are always shapeshifting across spacetime.”14

Enter spacetime

On 21st September 1908, Hermann Minkowski, a mathematician and former teacher of Albert Einstein, delivered an address at the 80th Assembly of German Natural Scientists and Physicians in Cologne, in which he introduced his theory of spacetime:

The views of space and time which I wish to lay before you have sprung from the soil of experimental physics, and therein lies their strength. They are radical. Henceforth space by itself, and time by itself, are doomed to fade away into mere shadows, and only a kind of union of the two will preserve an independent reality.15

In 1915, Einstein expanded on both Minkowski’s theory and his own earlier-proposed special theory of relativity, publishing The Foundation of the General Theory of Relativity. In it, he theorised that not only was spacetime a four-dimensional fabric, but that some of the most violent and energetic processes in the universe, events such as exploding stars and merging black holes, would create ripples in this fabric known as gravitational waves. A century later, Einstein’s theory was proven correct when researchers from the Laser Interferometer Gravitational-wave Observatory (LIGO) in 2015 made the first direct observation of gravitational waves, detecting faint ripples in spacetime caused by the collision of two black holes 1.3 billion years ago.16

The Dreaming Track in the Sky

Indigenous Australians had already been aware of the reality of spacetime for tens of millennia prior to Minkowski and Einstein’s discoveries. In their cultures, time has always been thick and multidimensional, “a pond you can swim through – up, down, around.”17 I am particularly fond of this metaphor – the way it invites you to dive right in actively encourages a deeper understanding of time as a fully immersive, spatial experience.

Researchers in cultural astronomy like astrophysicists Duane Hamacher, Kirsten Banks, and Krystal De Napoli have found many examples of discoveries attributed to modern Western science that had already been made by Aboriginal Australian peoples thousands of years ago. Their deep-time astronomical knowledge has developed over more than 65,000 years through detailed observation of the night skies. As oral traditions passed down from generation to generation, this knowledge represents a central component of Aboriginal Australian culture and cosmology and is woven into the stories of the Dreaming. 18

For example, in Wardaman traditions, the planets are ancestor spirits who walk along the Dreaming Track in the Sky, a celestial route familiar to Western astronomers as the ecliptic path of the sun. Wardaman Dreaming stories observe and clearly articulate the phenomenon known as retrograde motion, an optical illusion that causes the apparent backward motion of a planet, explaining it as the planet-ancestors slowing down and changing direction as they move both forwards and backwards on their cosmic journey.19 Differentiating between planets and stars and noting their changing positions relative to each other allows Aboriginal cultures to devise complex seasonal calendars.20 These are sometimes recorded in the landscape: or example, the Wurdi Youang stone arrangement built by the Wathaurong people indicates the positions of the setting sun at the solstices and equinoxes to mark the cycle of the year.21

II. Time-space synaesthesia

A further entanglement

Nancy Munn, a cultural anthropologist recognised for her ground-breaking, cross-cultural research into time and space, proceeds to tie yet another thread into Bo Bardi’s marvellous entanglement, Manning’s Dreaming knot, and Einstein and Minkowski’s fabric of spacetime, claiming that “In a lived world, spatial and temporal dimensions cannot be disentangled, and the two commingle in various ways.”22 Many people seem to sense some sort of implicit or explicit association between time and space, evidenced in everyday expressions commonly found across cultures, such as “back in the 90s,” or “in the months ahead.” 23 Certain individuals, however, experience this “commingling” to a much greater extent, demonstrating a conscious awareness of mappings between time and space caused by a condition known as time-space synaesthesia.24

A union of the senses

The term synaesthesia derives etymologically from New Latin, syn (joined) + aesthesia, from Greek aisthesis (sensation), and thus literally refers to a union of the senses. It describes a perceptual phenomenon believed to be caused by hyperconnectivity within the brain,25 which results in cross-activation and “cross-talk” between different brain regions and leads to unusual ways of sensing and experiencing the world.26 Julia Simner, a professor of neuropsychology specialising in multisensory research, writes that synaesthesia “is characterised by the pairing of particular triggering stimuli (or ‘inducers’) with particular resultant experiences (or ‘concurrents’).”27 These pairings can manifest in many forms, for example experiencing music (inducer) as colour (concurrent), or tasting words (concurrent) in poetry (inducer). In the case of time-space synaesthesia, time is the triggering stimulus, with space being the resultant synaesthetic experience. Estimates of the prevalence of time-space synaesthesia in the general population vary from an overly conservative 2.2 percent to as much as 29 percent,28 but whatever the actual percentage, it is a demographic of which I make up part.

Sensing time in space

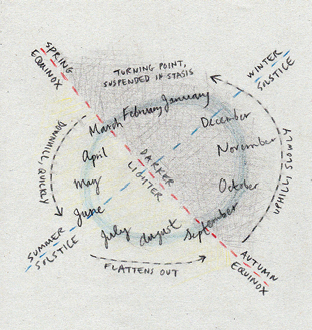

Like all individuals with time-space synaesthesia (also referred to as visuo-spatial synaesthesia), I experience units of time as forms or regions with a spatial layout. For as long as I can remember, I have perceived the months of the year arranged in a circle that I move through in an anti-clockwise direction (Figure B). January is at the top, with July and August at the bottom. The pace at which I progress through the different months is not constant, but varies depending on their position in the circle and relative to each other. There is a moment of stasis around January and February, when the movement slows right down. This marks a turning point – I feel myself suspended, the same kind of weightless inertia experienced at the highest point of a rollercoaster, right before gravity kicks in. Then, as the gravitational potential energy is transformed into kinetic, I descend quickly through the flush of spring and freefall quite effortlessly towards summer, my birthday marking the summer solstice as I arrive to the lowest part of my mental calendar but the high point of my year. There is another lull and slight deceleration as the circle flattens out and I coast along during the long days of the summer holidays. In September, with the start of the academic year – which as opposed to January represents for me the true beginning of a new cycle – I start to ascend again, slowly, as the days darken, trudging uphill to reach the shortest day on the winter solstice, heralding Christmas and the subsequent start of a new Gregorian calendar year.

Synaesthetic spatial configurations for time and calendar forms have been recorded as far back as the early nineteenth century. Although the positioning or form of the mappings is uniquely personal and differs from synaesthete to synaesthete, one characteristic feature used to diagnose time-space synaesthesia that differentiates it from other forms of strong mental imagery is that these arrangements remain highly consistent over time.29

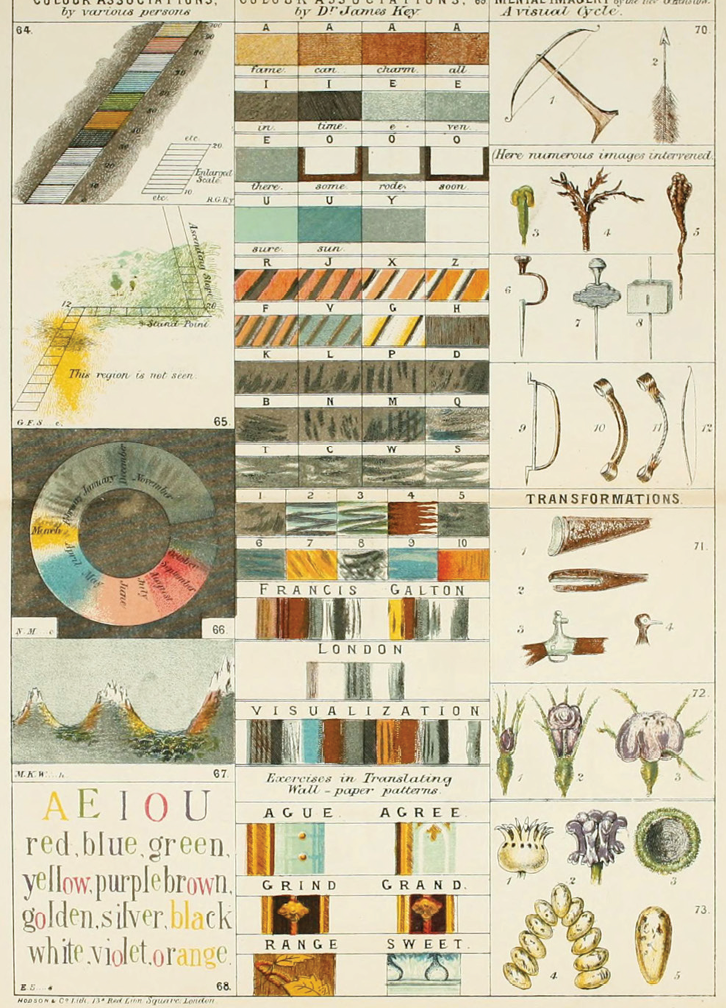

One of the earliest written descriptions of synaesthetic calendars, published by polymath Francis Galton30 in his 1883 book Inquiries into Human Faculty and Its Development, reveals both similarities and differences when compared to my own:

The months of the year are usually perceived as ovals, and they as often follow one another in a reverse direction to those of the figures on the clock, as in the same direction. It is a common peculiarity that the months do not occupy equal spaces, but those that are most important to the child extend more widely than the rest. There are many varieties as to the topmost month; it is by no means always January.31

A visuo-spatial continuum

While I often say that I “envisage” my calendar array, I realise that this is perhaps not the most accurate word to use, because it places undue emphasis on visualisation. Visuo-spatial synaesthesia is a continuum,32 and while some time-space synaesthetes can describe very definite visual features, for me it is more of a spatialisation, since while I am aware of the months and their positions, I find it difficult to provide a visual description of the actual months themselves – for me, they have no particular shape or colour, but rather represent regions in space that are definite, constant, and unchanging.

I do, however, sense areas of the circle as being darker or lighter – the half of the circle between October and February is perceptibly and noticeably darker than the section between March and September, more or less aligned with the spring and autumn equinoxes in the northern hemisphere, presumably a subconscious interiorisation of the shorter and darker days outside.

The summer months have always been brighter in my mind and in my memory, so it makes sense that the winter months would naturally be darker by comparison. When I was 14 years old, I suffered for the first time from seasonal affective disorder or SAD, a type of depression influenced by seasonal patterns, where symptoms are usually more apparent and severe during the winter months. Since then, the difference in brightness between the two halves of the year on my synaesthetic calendar has become more pronounced, and while SAD has never affected me again to the same extent, there are still years when I experience less intense bouts.

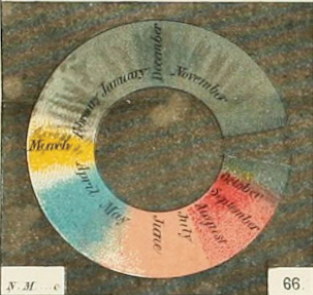

Pause

Upon reaching the final pages of Galton’s book, I am struck by a very beautiful hand-illustrated plate (Figure C). Galton writes, “Figs. 66, 67. These two are selected out of a large collection of coloured Forms in which the months of the year are visualised. They will illustrate the gorgeousness of the mental imagery of some favoured persons.”33 The configuration of Figure 66 (Figure D) is strikingly similar to my own calendar: the months are arranged anti-clockwise in a circle, with January at the top left, and from here all of the months are found in more or less the same positions as I perceive them, albeit shifted slightly further anti-clockwise. Even more surprisingly, even though unlike me this synaesthete associates certain months with a specific colour – March is yellow; April and May are light blue; June and July salmon pink; with August, September, and October all a reddish hue – the half of the calendar between the end of October and the start of March is noticeably darker, coloured a murky grey. This gives me pause – it is quite a strange sensation to discover that this person, described by Galton only as “the wife of an able London physician,” living in a different country a full century before I was born, experienced the months of the year in a very similar way to how I do. I feel a strange affinity with this mystery woman, as if we somehow share a common connection that allows us to navigate our inner and outer spacetimes.

Mental arrays

If I hear a popular song released any time in the past few decades, I will usually be able to recall with an uncanny degree of accuracy the year in which it was released. The same goes for films, family history, personal memories, and world events. Anecdotal reports suggest that an above-average memory for dates and events in visuo-spatial synaesthetes appears to be quite common. This led a group of scientists at the University of Edinburgh and the University of East London to test whether time-space synaesthetes do actually present cognitive benefits with regard to memory recall. Their hypothesis predicted that “synaesthetes will have superior performance in these tasks because their time-space arrays afford them an additional dimension (space) by which to encode or retrieve temporal information.”34

The results showed that synaesthetes did indeed show superior abilities in recalling temporal information, consistently out-performing non-synaesthete controls in accurately recalling dates of world events, films, and music. These abilities were not limited to simple date recall, since they were also able to recall on average almost twice as many autobiographical memories as non-synaesthetes.35

The phenomenology of this remarkable ability in time-space synaesthetes appears to be rooted in the spatialisation of temporal data – whether events, dates, or memories – which enables us to quickly retrieve them by determining their relative position to one another in our mental array. Simner notes that

When presented with a time period (e.g., a month of the year) time-space synaesthetes report that the associated spatial location is immediately brought to mind, and that they have a sophisticated ability to mentally manipulate the properties of this spatial representation. Specifically, synaesthetes claim to be able to manipulate the viewing-angle and size of their arrays, by taking multiple perspectives (or sometimes mentally re-orienting the array), or by “zooming in” on certain portions.36

For me at least, this ability has further applications: whenever I need to ground myself in a particular moment, I have a habit of zooming out, recalling and retrieving the location of a memory or momentous event. I calculate how far I am from that point by simultaneously checking where I was and what I was doing the same distance of time in the “opposite” direction, as a way to determine the relative position of the “now” where I find myself. I am always situated somewhere, somenow, but it is a position that I sense as much within the wider universe as inside my mind, and I cannot differentiate where one ends and the other begins

Involuntary projections

It is important to point out that the array inside my mind is not a “Memory Palace” in the strict sense of a method of loci. I don’t construct an imaginary version of an actual building or a familiar setting within which I assign images to set loci, locations that must always be visited in a particular sequence in order to retrieve different memories which are stored in each room. Time-space synaesthesia is not a conscious trick or mnemonic device employed to enhance memory recall through the creation of mental associations. Thus another characteristic that distinguishes the mental arrays of visuo-spatial synaesthetes from other types of mental imagery and visualisations is the fact that they are involuntary rather than conscious projections.

III. Thin places

A yellow car

I am sitting in the back seat of my parents’ car, an old yellow Ford Escort (Figure E) with a habit of breaking down in the most awkward places at the most inopportune moments. It is 1983, and we are driving along the Meadow Road to my aunt’s house. I am looking out the window at the sky (Figure F) when the row of purple sycamores planted along the edge of the football field suddenly flashes into view, forcing my eyes to adjust from their lazy gaze to dart between staccato bursts of leaves that punctuate a now-overexposed sky behind them. In a town where tree-lined roads are few and far between, the combination of the height and reach of those trees and the scintillating rhythm of shadow and light effects created by the movement of the car passing beneath them allows me to recognise where I am, and from that deduce where we are headed. Those trees were my first route markers, positioning devices that helped me begin to understand the spatiality of the world I found myself in; that car journey constituted an awakening of spatial awareness.

Revelations in motion

According to map-maker and author Tim Robinson, “Sometimes, changes in the relative position or apparent size of objects, caused by our own motion, reveal that motion to us at an unaccustomed level of consciousness, and bring the bare fact of motion, of position itself, into the light of attention.”37 Robinson wrote this while analysing a similar moment of cognisance of the “delicate and precise awareness of one’s spatial relationships to the world,”38 namely Marcel Proust’s recollection of the “special pleasure” he experienced on catching sight of the twin steeples of Martinville and that of Vieuxvicq, a triangulation in which they were “constantly changing their position with the movement of the carriage and the windings of the road”; Proust recalled, “In noticing and registering the shape of their spires, their shifting lines, the sunny warmth of their surfaces, I felt that I was not penetrating to the core of my impression, that something more lay behind that mobility, that luminosity, something which they seemed at once to contain and to conceal.”39

That something more, suggests Robinson, is the dawning realisation that “We are spatial entities [...] Our physical existence is at all times wrapped in the web of directions and distances that constitutes our space.”40

Solstice II

It is an afternoon in June 1983 or 1984, one week before the summer solstice. It is my birthday, and I am skipping excitedly down a tree-lined avenue (Figure G) with my cousin, coming home from the nursery school at the opposite end. I’m clutching a bag of sweets, swinging it in time with my steps, one of those cone-shaped plastic bags of marshmallows, pointed at the bottom end and twisted into a handle at the top, a present from the teachers. It is sunny, and the trees are scattering dappled shade, their leaves rustling softly in the breeze. I don’t recall noticing any of the houses, cars, or people that we pass, but I am distinctly aware of the trees arching high above me in a moiré-patterned vault of green and gold. My memory soaks up the light, the sounds, the warmth of the sun, the smell of the lime blossom, the pollen and feathery wishes41 floating on the air. These trees personify the avenue, my sense of home sheltered in their quiet, reassuring presence.

Of trees and planters

I was fortunate to grow up on one of the few tree-lined streets in our town (Figure H). This avenue originally led up to a “big house,” a term used by Irish people – “with a slight inflection – that of hostility, irony?”42 – to describe a mansion of the landed gentry. Before the much more modest houses of my parents and our neighbours were built along one side of the avenue in the early 1980s, it was known locally as Lovers’ Lane, a place where courting couples would dander43 on romantic strolls.

The English writer and horticulturist John Evelyn is credited as being the first person to use the term avenue, describing it in his 1664 book Sylva, or A Discourse of Forest-Trees as “the principal Walk to the Front of the House,”44 since avenues have historically been planted on the estates of the aristocracy to formally mark this particular route. According to Sarah M. Couch, an architect and specialist in the conservation of historic parks and gardens, they represent “a highly visible expression of man’s imposition of order over nature: an avenue could be seen as a symbol of control over the landscape and its inhabitants; an expression of ownership and power.”45

This was certainly the case with our avenue: the big house that it originally led to, Ashgrove, was built as the seat of the Carlile family, who arrived in the area from Scotland in 1611 at the beginning of the Plantation of Ulster,46 the most ambitious settler colonial project ever undertaken in Europe. The British Crown, with the aim of subjugating and consolidating control over what until then had been the most Gaelic and least anglicised province of Ireland, forcibly confiscated land from the indigenous population and granted it to “loyal” planters from England and Scotland “who would bring civility, order and the Protestant faith.”47 Viewing Ireland “as a country whose resources were there to be exploited for the economic benefit of Britain,”48 these planters set about altering the environment to achieve their aim, dramatically transforming not only the physical but also the demographic, political, religious, social, and cultural landscape.

Taming the wilderness

A familiar colonial narrative often employed to justify imperialism and the subjugation of indigenous populations – not only in Ireland, but also in the Americas, the Caribbean, Australia, Africa, the Middle East, and the Indian sub-continent – is the discourse of improvement. This constructs a dichotomy wherein the native landscape and people are characterised as wild and uncultivated, in contrast to the productive and civilising influence of the colonisers. By way of this narrative, explains archaeologist Joanna Brück, “the properties of the landscape become assimilated to the characteristics of its inhabitants.”49 In the colonial imagination, the savage nature of the landscape not only reflects the barbarous culture of its people, but the reverse is equally true.50

The elements of the Irish landscape that British colonialists most associated with the “wilde and barbarous”51 natives were the country’s woods and bogs, denounced in the 1601 Calendar of State Papers as “a great hindrance to us and a help to the rebel.”52 According to geographer and historian Eileen McCracken, they posed “a serious obstacle to the Tudor conquest and colonization of Ireland. The Irish had resisted the invaders from the shelter of the bogs and woods whenever possible.”53 This gave rise to a common English saying at the time: “The Irish will never be tamed while the leaves are on the trees.”54 The forests, along with those they harboured, became targets for eradication.

Ten thousand years ago, at the end of the last Ice Age, the island of Ireland was almost entirely covered in forest. Today, it has the lowest tree cover of any country in the European Union: a paltry 11 percent, compared to the European average of 33.5 percent. Less than 2 percent is native woodland, the rest mainly consisting of commercial conifer plantations.55 While deforestation had already been ongoing since the first Mesolithic farmers began clearing woodland for agriculture and grazing 7,000 years ago, it accelerated dramatically during the colonial period, as English and Scottish planters “spread across Ireland throughout the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, felling woodland at an incredible rate.”56 This systematic clearance can in part be attributed to military-strategic aims of eradicating the last refuges of the rebellious natives, but profit was also a motive – as McCracken states, “[t]he planters wanted to make money as quickly as possible and one of the easiest ways was to utilize the timber on their estates.”57

Of planters and trees

The devastating environmental effects of colonial exploitation reshaped the Irish landscape, but while the planters were content to plunder native woodlands, they “nonetheless valued biodiversity in their gardens.”58 Samuel Lewis reported in his 1837 Topographical Dictionary of Ireland that since the “ancient forests have long since been cleared away,” the only trees to be found “are in the neighbourhood of the mansions of the nobility and gentry.”59 Brück describes how the Anglo-Irish aristocracy planted trees around their estates to “relieve the eye from the dreariness and desolation of so much of the Irish countryside, providing an oasis of civilization and a little piece of Britain in this foreign country.”60 Having been extirpated from most of the landscape, trees now paradoxically came to symbolise the very plantations that caused their decimation. As a French visitor to Ireland in the late 1880s remarked, “The tree has become a lordly ensign. Wherever one sees it one may be certain the landlord’s mansion is not far.”61

A colonial inheritance

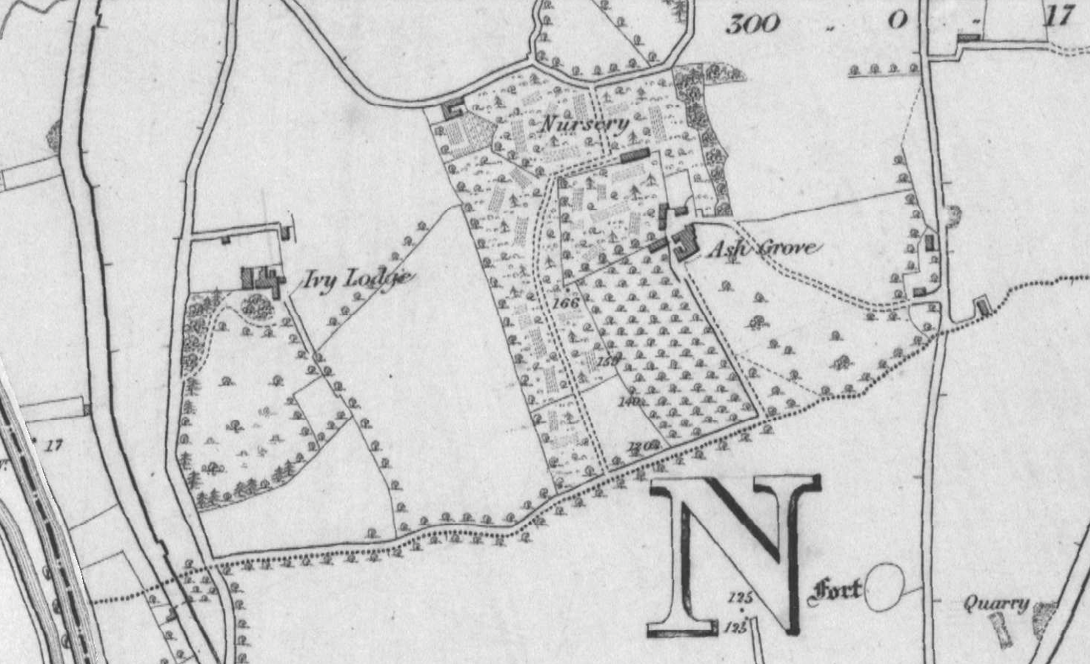

The trees on our avenue stand as testaments to this artificially planted colonial legacy. Exactly when they were laid out by the Carliles is uncertain, but a double row of trees can already be seen on the Ordnance Survey map of the area drawn between 1832 and 1846 (Figure I), so the surviving trees would appear to be at least 177 years of age, but are most likely older.

By the time my father set foot on the avenue in February 1982 to view a housing development he had seen advertised in the local paper, the Carliles and their big house had disappeared, and the trees on the south side of Lovers’ Lane had already been cut down to make way for the new houses. In order to secure the last of these on a corner plot, my father quickly engaged a solicitor, arranged a mortgage, and put down a deposit to buy the house before my mother – at that moment pregnant and confined to her bed – had even had a chance to see it.

Invisible ashes

As a child I was fascinated by nature – from books I taught myself the names of the wild birds, animals, and plants I would spot around our local area. For a long time I wondered why our avenue – which illustrated field guides helped me to identify was lined by lime trees – appeared to be named after a grove of ash trees that were nowhere to be found. Even when I learned that the avenue took its name from the big house it once led to, explorations of the surrounding grounds revealed only a few solitary oaks, with not a single ash in sight.

According to one Nicholas Carlisle62 writing in 1822, the Carlile family’s residence was originally known as Drumcashilone, “the name of the Townland upon which the Mansion is built, but, within the last fifty years, the Father of the present Proprietor changed its name to ‘Ashgrove.’”63 Researchers Anna Pilz and Andrew Tierney confirm that from around the mid-seventeenth century, the planting of trees on the estates of the gentry “was accompanied by a new fashion for renaming country houses after trees, part of the process of further Anglicizing the native landscape.”64 Hugh Carlile’s decision to rename Drumcashilone to Ashgrove was therefore not an isolated incident, neither was it an innocuous act; rather, it reflected a long-established and deliberate policy of anglicisation and erasure. “This was a process that had been going on piecemeal since the earliest days of the English colonization of Ireland, but now it was being implemented systematically,” writes Tim Robinson, that aforementioned triangulator of Proust; “As a result, over most of Ireland the placenames have lost their subtlety of sound […] and have been rendered meaningless, thereby shedding their load of historical, mythical and descriptive content.”65

Ironically enough, Robinson was an Englishman, one who lived the last four decades of his life on the Atlantic coast of Ireland, where in his own words he set himself the task

to restore the musical and memorious Gaelic placenames that had been traduced by the phonologically dim and semantically null anglicized forms given on the official Ordnance Survey maps. This project I thought of as political, in that it aimed to undo some of the damage of colonialism […] But inevitably it was also a rescue-archaeology of a shallowly buried sacred landscape.66

Landscape as memory

The term townland67 mentioned by Nicholas Carlisle represents the most basic unit of land division in Ireland. Townlands are ancient demarcations of place that usually take their names from identifiable natural or manmade features of the landscapes they mark, but they also often reference local genealogy and mythology. As such, these names “symbolize generations of memories rooted in places, a narrative of the intimate and mingled nature of that remembering,”68 all of which is alluded to in the Irish word for both topography and placelore, dinnseanchas.

Much as the ritualised memory of the Dreaming stories of Aboriginal Australians keeps alive the spirit of place, the oral tradition of dinnseanchas69 acts as custodian of the “sacred landscape” evoked by Robinson. An Foclóir Beag, The Little Dictionary translates dinnseanchas as “Lore about places, how they got their name, great events that happened there, etc.”70 The Irish-language poet Nuala Ní Dhomhnaill elaborates

In dinnsheanchas, the land of Ireland is translated into story: each place has history that is being continuously told […] The landscape itself, in other words, contains memory, and can point to the existence of a world beyond this one […] there is also an access to other times: there is a sense in which dinnsheanchas also mediates between past and present, and allows us glimpses into other moments in historical time.71

Other realms

Both dinnseanchas and the Dreaming take for granted the existence of realms other than the physical one we inhabit in our everyday lives. Indeed, the scientists operating the largest particle physics laboratory in the world suggest that it is entirely possible other dimensions exist, “but are somehow hidden from our senses.”72 Indigenous Australian cultures believe that the ancestral spirits of the Dreaming “still abound but are usually no longer visible, having withdrawn from human view into another space/time realm,” having gone into the ground.73 This is strikingly similar to the Celtic legend of the Aos Sí, a mythical race of supernatural beings descended from the Tuatha Dé Danann, the people of the goddess Danu. They were the inhabitants of the island of Ireland prior to the arrival of the Milesians, supposed ancestors of the present Irish population, with whom they came to an agreement that saw the Tuatha Dé Danann migrate underground to the Otherworld, a parallel universe separated from ours “by no barrier save concealment (díchelt).”74 Just as in the Dreaming, “in the Otherworld all of time exists simultaneously in an eternal present.”75

Thin places

“There are places,” writes Kerri ní Dochairtaigh, “which are so thin that you meet yourself in the still point. Like the lifting of the silky veil on Samhain, you are held in the space in between. No matter the past, the present or what is yet to come.”76

A thin place is a tear in the spacetime continuum, where two dimensions touch and bleed freely into one another, a point where it is possible to pass from one world to another. Thin places are thresholds – they can represent physical locations, but they can also be moments in the cycle of the year, like the feast of Samhain, an event in the Celtic calendar that marks the end of the lighter half of the year and the beginning of the darker half. Celebrated between 31st October and 1st November, it is a time when the boundaries of this world and the Otherworld are stretched so thin that the spirits can walk amongst us. Celtic folklore has a fascination with thresholds, recognising the advantage of inhabiting liminal spaces, of having a foot in more than one realm.

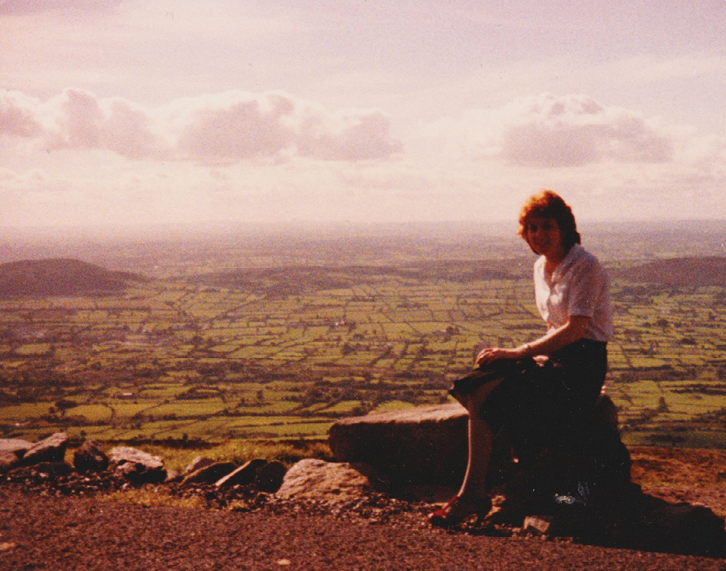

IV. Thick time

Concentric collapse

The area where I grew up is dominated by Slieve Gullion, an extinct volcano situated in the centre of a circle of smaller mountains, known as the Ring of Gullion, or Fáinne Cnoc Shliabh gCuillinn (Figure J). This remarkable landform is known as a ring dyke, and was formed hundreds of millions of years ago by a series of particularly violent volcanic eruptions in which the caldera of the volcano collapsed concentrically. The Ring of Gullion was the very first geological formation of this type to be mapped.77 At the summit is a crater or tarn lake and two ancient burial cairns (Figure K), the southernmost of which is the highest surviving passage tomb in Ireland, dating from between 4000 B.C. and 2500 B.C.78 Passage tombs are found all over the island and are held to be especially thin places, believed to be entrances to the Otherworld.79 It is easy to understand why – the Neolithic astronomers who built the cairn on Slieve Gullion aligned it so that on the winter solstice, the setting sun shines through the passage to illuminate the chamber at the centre of the tomb, a phenomenon also witnessed with the rising sun at the much more well-known tomb at Newgrange.

Intimate relay

Slieve Gullion has been described as “perhaps the most mystic of our Irish mountains,”80 providing the setting for some of the most famous Celtic legends. According to myth, the mountain’s name comes from Sliabh Cuilinn, Culann’s Mountain, referring to the metalsmith whose ferocious guard dog was killed by the legendary hero Sétanta, son of the sun god Lú, while Sétanta was still only a boy. This event led to him receiving his unusual adult name, Cú Chulainn, the Hound of Culann. Others maintain that Slieve Gullion is an anglicisation of Sliabh gCuillinn, meaning “mountain of the steep slope,”81 referring to the mountain’s geological feature of a crag and tail formed by glacial erosion.

This blurring of topography, toponymy, mythology, and geology is typical of dinnseanchas and reflects how the real and imagined, the tangible and the intangible, the natural and the supernatural become inseparable, interlaced in an intimate relay where it is impossible to tell which came first, where legend ends, and where landscape begins.

Time mirrored

In the spring of 2017, almost a year after the Brexit referendum, I visited the Wolfgang Tillmans exhibition at the Tate Modern in London. A work entitled Time Mirrored, a series of short reflections on time that juxtaposed historical events and periods in relation both to each other and to the present day, sparked a flash of recognition.

1969 was 24 years away from 1945

24 years back from now is 1992

1991 was the year the Cold War ended after 44 years

44 years ago was the year 1972

Surprised to see someone else employing what to me is a very familiar methodology, I sought out more information on the artist’s thought process. On the Tate website Tillmans explains, “I’ve written about time and the relative distances of time spans in order to remind myself of how much today is actually the history of tomorrow,” 82 presenting examples to describe how the same time span can feel longer or shorter depending on the events that occurred between then and now, and how certain years appear closer or further away depending on their significance to one’s personal life.

According to the Tate Modern’s press release, Time Mirrored “represents Tillmans’s interest in connecting the time in which we live to a broader historical context […] Events perceived as having happened over a vast gulf of time between us and the past, become tangible when ‘mathematically mirrored’ and connected to more recent periods of time in our living memory.”83

During an earlier solo exhibition at the Serpentine Gallery in 2010, Tillmans described an approach to his art that reveals strong polychronic tendencies: “I try to approximate the way I see the world, not in a linear order but as a multitude of parallel experiences. Multiple singularities, simultaneously accessible as they share the same space.”84

Triangulation, trilateration, parallax

I wonder if Tillmans might be a time-space synaesthete, given how his practice of situating the current moment or placing a past event by projecting an equal distance both backwards and forwards in time uncannily parallels how I navigate the spacetime of my memory. It is a method comparable to triangulation, the technique of determining the location of a point from two known points on a baseline, although technically my method is closer to trilateration, since it depends on distances rather than angles. A third and perhaps more accurate analogy might be that of parallax, whereby a position can be determined through a change in viewpoint due to the motion of the observer (in my case through time as well as space, albeit both in the mind). In fact, the human brain utilises a combination of parallax – viewing from two or more successive vantage points – and stereopsis – viewing from two vantage points simultaneously – to perceive depth and gauge distances in the external world around us.85 In a sense, my spacetime parallax constitutes an interiorisation of a normally exterior function for positioning and perception.

Another yellow car

Four full decades after our yellow car drove under a row of purple sycamores to evoke my epiphany of spatial awareness, I find myself sitting in an Art Deco cinema unexpectedly reliving almost the same moment inside another yellow car. The film An Cailín Ciúin (The Quiet Girl) is an adaptation of Claire Keegan’s 2010 novella Foster. Set in Ireland in 1981, one of the earliest scenes faithfully depicts the opening pages of the book, when the narrator describes the view from the back seat of the car bringing her to stay with relatives in the countryside: “looking up through the rear window. In places there’s a bare, blue sky. In places the blue sky is chalked over with clouds, but mostly it is a heady mixture of sky and trees scratched over by ESB wires.”86

Immediately after the film ends, my friends and I discuss how accurately it managed to capture the minutiae of an 1980s Irish childhood, down to the Kimberley biscuit placed gingerly on the kitchen table. Discussing nostalgia, I am surprised to hear that the scene that resonated the most was the one in the car. Further research revealed my friends and I were not the only ones with whom it struck a chord – many critics and reviewers have singled out this particular scene for its dreamlike quality, remarking on how it captures “the kind of stray, ephemeral details that burn into a child’s memory.”87

Director Colm Bairéad explains, “I knew that in the car, the camera would never leave the backseat. That’s kind of the key to why the film works: It inhabits this young girl’s point of view and it never leaves her orbit.”88 Through the addition of movement and time, Bairéad’s film transposes the child’s-eye perspective captured so believably in Keegan’s writing into the fourth dimension. I realise it is this instance of parallax triggering an associated remembrance of a previous sensation, one that consciousness cannot fully grasp, that causes this scene to resonate so deeply.

Phantom touch

Every so often – it happens only a few times a year – I suddenly experience a very powerful sensation of touching or holding something in my hands that triggers a memory or recognition. Ironically, while my hands seem to remember the sensation – the shape, weight, firmness, texture, pliability, sometimes even temperature – my brain can never quite seem to put an idiomatic finger on exactly what the memory that I feel in my hands is, so I can never identify it by registering an image or a name. This phantom touch eludes every other sense, and even the tactile memory recedes and disappears as fleetingly as it arrived. I rack my brain, yet it is always too late to reconcile this sensation to the corresponding memory, but the sensation and recognition is so powerful, no matter how brief, that I am sure that my touch is actually triggered – it is somehow as if both imagined and yet not just in my imagination.

An impossible visualisation

The sensation is similar when I sit down to draw my internal spatial array for anything more complicated than the months of the year. I realise something quite unexpected – it is extremely difficult to transcribe the multidimensional space of my mind onto the page in front of me. As I try to visualise it more clearly in my mind’s eye, it keeps moving in and out of focus. Yet at the same time, the overall layout of the array does not change – the different points and events are in exactly the same positions relative to one another. If I could somehow take a screen shot inside my mind, that might help me to freeze my point of view and allow me to visually represent these spatialisations. But even closing my eyes and concentrating as hard as I can to force it into a one-, two-, or three-dimensional graphical form, one that my pen can record on the paper, brings me nothing but frustration coupled with a sore head.

I empathise with Augustine’s inability to describe time: I never imagined it would be so difficult to convey or map my mental array. As soon as I try to concentrate on it, it stubbornly disappears from view, as if it submerges or fades back into the mist, the ether, or a protean pool of amniotic fluid. It is the same sense of elusion felt when trying to recall a dream, or when re-experiencing the familiar impossibility of carrying something across the threshold from a dream to the waking world.

Relative point of view

Reflecting on this, I come to the conclusion that the reason for this inability to represent my mental array is that it constitutes a spatial experience rather than a purely visual one. It’s not so much that I conjure these units of time, these palimpsests of past events and memories as visions in what is commonly referred to as my mind’s eye, but rather that they exist independently as entities, and I am positioned in relation to them in the space of my mind, and this mindspace is both multisensory and multidimensional – my point of view will always be relative to all of them and they will always be relative to one another.

This offers the best explanation I can think of as to why I can so easily sense and understand positions, relations, distances, but drawing them proves so elusive. They do not lend themselves to a frustratingly flat, one-dimensional view that does not change in relation to my position or point of view – they form an array that I can move around, look through, zoom in to and out from, move through, much like in the flyover mode of a 3D CAD program. They are not projections on a screen or surface, but a thick spacetime whose multidimensions I am fully immersed in.

The unobservable fourth dimension

Researching further helps me to understand and accept the impossibility of trying to properly convey my own personal spacetime. The scientists at the European Organisation for Nuclear Research, more commonly known as CERN, confirm that “In everyday life, we inhabit a space of three dimensions,” those spatial dimensions being height, width, and depth. “Less obviously,” they continue, “we can consider time as an additional, fourth dimension, as Einstein famously revealed.”89 The problem is, much like the Celtic Otherworld or the sky-world of Aboriginal cosmology, we cannot directly observe this fourth temporal dimension, although we can speculate on it without actually perceiving it. Einstein himself made it quite clear in an 1929 interview that “No man can visualize the fourth dimension, except mathematically.”90 John D. Norton, Professor of the history and philosophy of science at the University of Pittsburgh and an expert on relativity and quantum theory, confirms that “There is no easy way to draw a picture of a four dimensional spacetime. Visualizing it can be very hard […] It is just another sort of space that happens to transcend simple visualization.”91

An entangling crisis unfolds

Exactly two decades ago, when I had already left home for university, my family moved out of the house on the avenue, two decades after we first moved in. The photo in Figure L was taken one spring in the early 2000s, shortly before we left. Since it was taken, much has changed: the tall lime trees at this end of the avenue have been felled, and the garden of the bungalow opposite, for years lovingly tended by our former neighbours, has been flattened by the new occupant, who tarmacked over the entire surface, ripped out the hedge along with the snowdrops and bluebells it once sheltered, enclosing his barren yard with a wall topped with spikes (Figure M). From the sublime to the ridiculous, from a corner of paradise to a prison car park. While I mourn the lost verdure of our neighbours’ garden and the refuge it provided for so many bird, insect, plant, and animal species, the sight of the avenue denuded of its trees cuts even more deeply, a bleak scene no longer recognisable as the setting of my childhood.

Faced with this environmental destruction on my doorstep, a microcosm of the wider biodiversity crisis unfolding before all our eyes, I remember Astrida Neimanis and Rachel Loewen Walker writing about how “climate change can become palpable in the everyday.”92 In order to draw attention to the many interconnected temporalities – circadian, arboreal, geological, cosmic – and cumulative actions responsible for the climate crisis, they propose a non-linear transcorporeality of thick time stretching between present, future, and past. Positioning ourselves “right in the thick of things,”93 they argue, allows us to understand how embodied human experience is inseparable from nature and our environment, and that the disentanglement of climate change and anthropogenic influences is impossible. Thick time “denies the myth that human bodies are discrete in time and space, somehow outside of the natural milieu that sustains them and indeed transits through them.”94

Solstice III

It is another evening in summer, my fifth birthday party. The game of pass-the-parcel has been rigged to ensure that the last and best parcel, containing a one-pound coin, lands on my lap. Still too young to appreciate the concept of money, I can’t understand why I didn’t win sweets like everybody else, on my birthday of all days. Furious and upset, I run outside to the bottom of the garden where I sit and sulk in self-pity. I stubbornly reject the advances of anyone who attempts to coax me back to my own party, until eventually my mother’s youngest brother gives it a try. Almost four decades after this, he will fight a short battle with a rare and particularly aggressive cancer and I will cut short a trip to the Arctic Circle to attend his funeral in the shadow of Slieve Gullion, but today he is in his early twenties, youthful and handsome. Looking back at photos, he could be an American television star. He is one of the youngest adults at the party, the cool uncle, so I listen as he explains that with the money I have just won, that boring old coin, I can buy more sweets than all of the rest of the prizes combined. This convinces me. He takes my hand, and together we go back inside.

1 Kerri ní Dochairtaigh, Thin Places (Edinburgh: Canongate Books, 2021), 4.

2 Barbara Adam, “Perceptions of Time,” in Companion Encyclopaedia of Anthropology, ed. Tim Ingold (Oxon: Routledge, 2002), 503.

3 St Augustine, Confessions, trans. R. S. Pine-Coffin (Harmondsworth: Penguin Books, 1961), Bk. XI, 14.

4 Carlo Rovelli, The Order of Time, trans. Erica

Segre and Simon Carnell (London: Allen Lane, 2018), 2.

5 Edward T. Hall, The Dance of Life: The Other Dimension of Time (New York,: Anchor Press/Doubleday, 1983), 45.

6 Hall, 43.

7 Hall, 45.

8 Adam, 503.

9 Adam, 504.

10 Jeremy Till, “Thick Time: Architecture and the Traces of Time,” in Intersections: Architectural Histories and Critical Theories, eds. Iain Borden and Jane Rendell (London: Routledge, 2000), 290.

11 Till, 291.

12 Marcelo C. Ferraz, ed., Lina Bo Bardi (São Paulo: Instituto Lina Bo Bardi e Pietro M. Bardi, 1993), 333.

13 Aleksandar Janca and Clothilde Bullen, “The Aboriginal Concept of Time and Its Mental Health Implications,” supplement, Australasian Psychiatry 11, no. 1 (2003): S41.

14 Erin Manning, Relationscapes: Movement, Art, Philosophy (Cambridge: MIT Press, 2012), 467.

15 Hermann Minkowski, “Space and Time,” in The Principle of Relativity: A Collection of Original Memoirs on the Special and General Theory of Relativity, ed. H. A. Lorentz, A. Einstein, H.

Minkowski, and H. Weyl, trans. W. Perrett and G. B. Jeffery (New York: Dover Publications Inc, 1952): 75.

16 Caltech, “2017 Nobel Prize in Physics Awarded to LIGO Founders,” press release, accessed September 11, 2023, https://www.ligo.caltech.edu/page/press-release-2017-nobel-prize#cit.

17 Janca and Bullen, 41.

18 Duane Hamacher and Krystal De Napoli, “The Rapidly Growing World of Indigenous Astronomy,” Free Astronomy Public Lectures,

Swinburne University of Technology, Centre for Astrophysics & Supercomputing, June 1, 2018, audio-recording 1:08:54, https://australian-podcasts.com/podcast/free-astronomy-public-lectures/the-rapidly-growing-world-of-indigenous-astronomy-.

19 Duane Hamacher, “Aboriginal Traditions Describe the Complex Motions of Planets, the ‘Wandering Stars’ of the Sky,” The Conversation, August 15, 2008, https://theconversation.com/aboriginal-traditions-describe-the-complex-motions-of-planets-the-wandering-stars-of-the-sky-97938.

20 Raymond Haynes, Roslynn D. Haynes, David Malin, and Richard McGee, Explorers of the Southern Sky: A History of Australian Astronomy (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1996), 8.

21 Reg Abrahams, Duane W. Hamacher, Cilla Norris, and Ray P. Norris, “Wurdi Youang: An Australian Aboriginal Stone Arrangement With Possible Solar Indications,” Rock Art Research 30, no. 1, (2013): 64.

22 Nancy Munn, “The Cultural Anthropology of Time: A Critical Essay,” Annual Review of Anthropology 21 (1992): 94.

23 Julia Simner, Neil Mayo, and Mary-Jane Spiller,“ A Foundation for Savantism? Visuo-Spatial Synaesthetes Present with Cognitive Benefits,” Cortex 45, no. 10 (November-December 2009): 1247.

24 Simner, Mayo, and Spiller, 1246.

25 Romke Rouw and H. Steven Scholte, “Increased Structural Connectivity in Grapheme-Color Synaesthesia,” Nature Neuroscience 10, no. 6 (June 2007): 792.

26 Julia Simner, “Defining Synaesthesia,” British Journal of Psychology, 103 (2012): 9.

27 Simner, Mayo, and Spiller, 1246.

28 Andrew M. Havlik, Duncan A. Carmichael, and Julia Simner, “Do Sequence-Space Synaesthetes Have Better Spatial Imagery Skills? Yes, but There Are Individual Differences,” Cognitive Processing 16 (2015): 245.

29 Simner, Mayo, and Spiller, 1247.

30 Galton also holds the rather dubious honour of being recognised as the founder of eugenics.

31 Francis Galton, Inquiries into Human Faculty and Its Development (New York: Macmillan, 1883), 124.

32 Clare N. Jonas and Mark C. Price, “Not dAll Synesthetes Are Alike: Spatial vs. Visual Dimensions of Sequence-Space Synaesthesia,” Frontiers in Psychology, 5, no. 776 (October 2014), https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2014.01171.

33 Galton, 146.

34 Simner, Mayo, and Spiller, 1251.

35 Simner, Mayo, and Spiller, 1255.

36 Simner, Mayo, and Spiller, 1250.

37 Tim Robinson, Setting Foot on the Shores of Connemara & Other Writings, (Dublin: The Lilliput Press, 1996): 104.

38 Robinson, Setting Foot on the Shores of Connemara, 105.

39 Marcel Proust, In Search of Lost Time, Volume 1, Swann’s Way, trans. C. K. Scott Moncrieff and Terence Kilmartin (New York: The Modern Library, 1992), 254.

40 Robinson, Setting Foot on the Shores of Connemara, 105.

41 A wish is a colloquial name for the silky pappus-clad, wind-dispersed seeds of thistles, dandelions and similar flowers, derived from the wish supposedly granted you upon catching one.

42 Elizabeth Bowen, “The Big House,” The Green Book: Writings on Irish Gothic, Supernatural and Fantastic Literature, no. 9 (2017): 86.

43 A dander is a gentle meandering walk with no particular haste or purpose, https://en.wiktionary.org/wiki/dander.

44 John Evelyn, Sylva, or A Discourse of Forest-Trees (London, I664), xcix.

45 Sarah M. Couch, “The Practice of Avenue Planting in the Seventeenth and Eighteenth Centuries,” Garden History 20, no. 2 (1992): 173.

46 Nicholas Carlisle, Collections for a History of the Ancient Family of Carlisle (London: W. Nicol, 1822), 201.

47 Jonathan Bardon, The Plantation of Ulster: War and Conflict in Ireland (Dublin: Gill & Macmillan, 2012), Chapter 1.

48 Joanna Brück, “Landscape Politics and Colonial Identities: Sir Richard Colt Hoare’s Tour of Ireland, 1806,” Journal of Social Archaeology, 7, no. 2 (June 2007): 228.

49 Brück, 230.

50 Stiofán Ó Cadhla, Civilizing Ireland: Ordnance Survey 1824-1842: Ethnography, Cartography, Translation (Dublin: Irish Academic Press, 2007), 111.

51 William Camden, Britain, or A Chorographicall Description of the Most Flourishing Kingdomes, England, Scotland, and Ireland (London: George Latham, 1637), 105.

52 Calendar of the State Papers Relating to Ireland, of the Reigns of Henry VIII, Edward VI., Mary, and Elizabeth, 1601–3 (London: Longman, H.M.S.O, 1912), 253.

53 Eileen McCracken, “The Woodlands of Ireland Circa 1600,” Irish Historical Studies 11, no. 44 (September 1959): 287.

54 William Edward Hartpole Lecky, A History of Ireland in the Eighteenth Century, New Impressions, vol. I (London: Longmans, 1913), 333.

55 Richard Nairn, “A Brief History of Ireland’s Native Woodlands,” Coillte Nature, October 19, 2020, https://www.coillte.ie/a-brief-history-of-irelands-native-woodlands/.

56 Eoin Neeson, “Woodland in History and Culture,” in Nature in Ireland: A Scientific and Cultural History, eds. John Wilson Foster and Helena C.G. Chesney (Dublin: Lilliput Press, 1997),

141.

57 McCracken, 289.

58 Keith Pluymers, “Taming the Wilderness in Sixteenth- and Seventeenth-Century Ireland and Virginia,” Environmental History 16, no. 4 (October 2011): 613.

59 Samuel Lewis, Topographical Dictionary of Ireland (London: S. Lewis and Co., 1837), 522.

60 Brück, 230.

61 Philippe Daryl, Ireland’s Disease; Notes and Impressions. The Author’s English Version (London: George Routledge and Sons, 1888), 52–53.

62 The Carlile family name seemed to have many spellings, Carlisle and Carlyle being two variations.

63 Carlisle, 201.

64 Anna Pilz and Andrew Tierney, “Trees, Big House Culture, and the Irish Literary Revival,” New Hibernia Review/Iris Éireannach Nua 19, no. 2 (Samhreadh/Summer 2015): 67.

65 Tim Robinson, “An Interview with Tim Robinson,” by Brian Dillon, Field Day Review 3 (2007): 38.

66 Tim Robinson, My Time in Space, (Dublin: The Lilliput Press, 2001), 95.

67 From the Irish baile fearainn, meaning land, territory or quarter.

68 Bryonie Reid, “‘That Quintessential Repository of Collective Memory’: Identity, Locality and the Townland in Northern Ireland,” in Senses of Place, Senses of Time, eds. Brian Graham and G. J. Ashworth (Oxon: Routledge, 2016), 55.

69 Also spelled dinnsheanchas

70 https://www.teanglann.ie/en/fb/dinnseanchas.

71 Nuala Ní Dhomhnaill, Selected Essays, ed. Oona Frawley (Dublin: New Island, 2005), 159–60.

72 “Do We Really Only Live in Three Dimensions?” CERN, February 17, 2012, https://cmsexperiment.web.cern.ch/index.php/physics/do-we-really-live-only-three-dimensions.

73 Dianne Johnson, Night Skies of Aboriginal Australia: A Noctuary (Sydney: Sydney University Press, 2014), 22.

74 John Carey, “Time, Space, and the Otherworld,” Proceedings of the Harvard Celtic Colloquium, Vol. 7 (1987): 7.

75 Carey, “Time, Space, and the Otherworld,” 8.

76 Ní Dochairtaigh, xvi.

77 Sadhbh Baxter, A Geological Field Guide to Cooley, Gullion, Mourne & Slieve Croob (Dublin: Geological Survey of Ireland, 2008): 44.

78 “Winter Solstice – Setting Sun Illuminates Slieve Gullion Passage Tomb,” Ring of Gullion, December 25, 2012, https://ringofgullion.org/news/winter-solstice-setting-sun-illuminates-slieve-gullion-passage-tomb/.

79 John Carey, “The Location of the Otherworld in Irish Tradition,” in The Otherworld Voyage in Early Irish Literature, ed. J. Wooding (Dublin: Four Courts, 2000), 118.

80 T. G. F. Paterson, Country Cracks; Old Tales from the County of Armagh (Dundalk: W. Tempest, Dundalgan, 1939), 44.

81 “Slieve Gullion,” Northern Ireland Place-name Project, accessed 3 April 2023, https://experience.arcgis.com/experience/9b31e0501b744154b4584b1dce1f859b/page/Place-Name-Info/?data_id=dataSource_1-PlaceNames_Gazeteer_No_Global_IDs_3734%3A23950.

82 “Studying Truth with Wolfgang Tillmans,” Tate Modern Museum, accessed April 10, 2023, http://tate-tillmans.s3-website.eu-west-2.amazonaws.com/.

83 ”Wolfgang Tillmanns: 2017,” Tate Modern, press release, accessed 10 April 2023, https://artblart.com/tag/wolfgang-tillmans-truth-study-center/.

84 “Wolfgang Tillmans, Truth Study Center, Tate 2017,” Tate Modern, April 2018, https://www.tate.org.uk/art/artworks/tillmans-truth-study-center-tate-t15603.

85 Barbara Gillam, “Stereopsis and Motion Parallax,” Perception, 36, no. 7 (2007): 953.

86 Claire Keegan, Foster (London: Faber & Faber, 2010), 3.

87 Sean Burns, “’The Quiet Girl’ Is a Deceptively Simple Story about Unexpected Kindness,” review of The Quiet Girl, dir. Colm Bairéad, WBUR, February 28, 2023, https://www.wbur.org/news/2023/02/28/the-quiet-girl-colm-bairead-film-review.

88 Colm Bairéad, “Irish Oscar Entry ‘The Quiet Girl’ Has a Secret Weapon: Silence,” interview by Steve Pond, The Wrap, December 7, 2022, https://www.thewrap.com/the-quiet-girl-director-colm-bairead-interview/.

89 “Do We Really Only Live in Three Dimensions?”

90 Colm Bairéad, “Irish Oscar Entry ‘The Quiet Girl’ Has a Secret Weapon: Silence,” interview by Steve Pond, The Wrap, December 7, 2022, https://www.thewrap.com/the-quiet-girl-director-colmbairead-interview/.

91 John D. Norton, “Spacetime,” University of Pittsburgh Department of History and Philosophy of Science, accessed 14 April 2023, https://sites.pitt.edu/~jdnorton/teaching/HPS_0410/chapters/spacetime/index.html.

92 Astrida Neimanis and Rachel Loewen Walker, “Weathering: Climate Change and the ‘Thick Time’ of Transcorporeality,” Hypatia:

A Journal of Feminist Philosophy 29, no. 3 (Summer 2014): 562.

93 Neimanis and Walker, 569.

94 Neimanis and Walker, 563.

Colm Mac Aoiḋ

University of Hasselt, Faculty of Architecture and Arts

Visuo-spatial or time-space synaesthetes visualise and position abstract units of time as mappings in the virtual space of their mind, effectively sensing time in space. In Parables for the Virtual: Movement, Affect, Sensation, Brian Massumi identifies a “liminal nonplace” that “lies at the border of what we think of as internal, personal space and external, public space.”1 Rather than nonplace, a more apt description might be a thin place, where two dimensions touch and bleed freely into one another.2

This paper explores the correspondence between the mental, inner spaces of time-space synaesthetes and the physical spaces in the “real” world around them, examining the ways in which these different dimensions overlap, inhabit one another, and ultimately collapse into the unified and unique experience of human perception.

The journey starts from my own experience, describing my personal spatial configurations for time and memory and how I rely on these to situate myself and navigate a path through life. Along the way I connect with other stories – including from friends and family, the Indigenous Australian concept of the Dreaming, the Irish topographic and toponymic tradition of dinnseanchas, Minkowski and Einstein’s theory of spacetime, Wolfgang Tillman’s Time Mirrored, and Tim Robinson’s “deep mapping” – to illustrate how lived experience takes place in a space that is simultaneously tangible and intangible, flowing freely between inner and outer worlds and combining multiple senses, tenses, and dimensions.

1 Brian Massumi, Parables for the Virtual: Movement, Affect, Sensation (London: Duke University Press, 2002), 186.

2 Laura Béres, “A Thin Place: Narratives of Space and Place, Celtic Spirituality and Meaning,” Journal of Religion and Spirituality in Social Work 31, no. 4 (October 2012): 394-413.

time, memory, synaesthesia, spacetime, decoloniality, indigenous knowledge.

Figure A: View of an upstairs window inside the house where I grew up, looking to the garden beyond. Photo by the author.

Figure B: Sketch of my synaesthetic calendar, 2023. Image by the author.

Figure C: Plate IV from Galton’s book, Inquiries into Human Faculty and Its Development. Licence: Public domain.

Figure D: Detail of Fig. 66 from Galton’s Plate IV

Figure E: The yellow Ford Escort owned by my parents in the early 1980s. Family photo.

igure F: Blurry shot from the back seat of our yellow car in motion, early 1980s. Family photo.

Figure G: Poorly-exposed photograph of the lime trees on our avenue, early 1980s. Family photo.

Figure H: Playing in our garden with the avenue of lime trees in the background, mid-1980s. Family photo.

Figure I: Ordnance Survey map from 1832–1846, showing a row of trees planted on either side of the avenue that runs from southwest to northeast on the main approach to Ashgrove estate (here labelled Ash Grove); while the grounds of the estate abound with trees and even contain a plant nursery, trees are noticeably absent from the surrounding landscape. © Ordnance Survey Ireland / PRONI Historical Maps.

Figure J: Photo of my mother taken close to the summit of Slieve Gullion, with the mountains of the Ring of Gullion visible in the background as a circle of dark hills, early 1980s. Family photo.

Figure K: My father and I on the summit of Slieve Gullion in 1981, standing beside the southern cairn with the crater or tarn lake in the near distance and the Ring of Gullion just about visible in the background. Family photo.

Figure L: Photo taken looking from our garden to the Western end of the avenue in springtime, early 2000s. Photo by the author.

Figure M: Photo taken of the same view in April 2023. Photo by the author.

Colm mac Aoiḋ is a Brussels-based transdisciplinary practitioner, researcher and writer working across design, communication, architecture and urbanism. He studied Visual Communication Design at Dublin Institute of Technology, followed by Architecture and Sustainability at London Metropolitan University and Sint-Lucas/KU Leuven. He worked as an architect in London and Ghent before collaborating with the team of the Brussels Bouwmeester Maitre Architecte, in consortium with UN-Habitat and University College London, on the Horizon 2020 Urban Maestro project to explore and encourage innovation in urban design governance. He is currently a PhD researcher at Hasselt University, where he is investigating strategies for adaptive reuse as part of the research group Trace.

REFERENCES

Abrahams, Reg, Duane W. Hamacher, Cilla Norris, and Ray P. Norris. “Wurdi Youang: An Australian Aboriginal Stone Arrangement With Possible Solar Indications.” Rock Art Research 30, no. 1 (2013): 55–65.

Adam, Barbara. “Perceptions of Time.” In Companion Encyclopaedia of Anthropology, edited by Tim Ingold, 503–26. Oxon: Routledge, 2002.

Bairéad, Colm. “Irish Oscar Entry ‘The Quiet Girl’ Has a Secret Weapon: Silence.” Interview by Steve Pond. The Wrap, December 7, 2022. https://www.thewrap.com/the-quiet-girl-director-colm-bairead-interview/.

Bardon, Jonathan. The Plantation of Ulster: War and Conflict in Ireland. Dublin: Gill & Macmillan, 2012.

Baxter, Sadhbh. A Geological Field Guide to Cooley, Gullion, Mourne & Slieve Croob. Dublin: Geological Survey of Ireland, 2008.

Béres, Laura. “A Thin Place: Narratives of Space and Place, Celtic Spirituality and Meaning.” Journal of Religion and Spirituality in Social Work 31, no. 4 (October 2012): 394–413.

Bowen, Elizabeth. “The Big House.” The Green Book: Writings on Irish Gothic, Supernatural and Fantastic Literature, no. 9 (2017): 85–91.

Brück, Joanna. “Landscape Politics and Colonial Identities: Sir Richard Colt Hoare’s Tour of Ireland, 1806.” Journal of Social Archaeology 7, no. 2 (June 2007): 224–49.

Burns, Sean. “‘The Quiet Girl’ Is a Deceptively Simple Story about Unexpected Kindness.” Review of The Quiet Girl directed by Colm Bairéad. WBUR, February 28, 2023. https://www.wbur.org/news/2023/02/28/the-quiet-girl-colm-bairead-film-review.

Calendar of the State Papers Relating to Ireland, of the Reigns of Henry VIII, Edward VI., Mary, and Elizabeth, 1601–3. London: Longman, H.M.S.O, 1912.

Caltech. “2017 Nobel Prize in Physics Awarded to LIGO Founders,” press release, accessed September 11,2023. https://www.ligo.caltech.edu/page/press-release-2017-nobel-prize#cit.

Camden, William. Britain, or A Chorographicall Description of the Most Flourishing Kingdomes, England, Scotland, and Ireland. London: George Latham, 1637.

Carey, John. “The Location of the Otherworld in Irish Tradition.” In The Otherworld Voyage in Early Irish Literature, edited by J. Wooding, 113–19. Dublin: Four Courts, 2000.

Carey, John. “Time, Space, and the Otherworld.” Proceedings of the Harvard Celtic Colloquium 7 (1987): 1–27.

Carlisle, Nicholas. Collections for a History of the Ancient Family of Carlisle. London: W. Nicol, 1822.

Couch, Sarah M. “The Practice of Avenue Planting in the Seventeenth and Eighteenth Centuries.” Garden History 20, no. 2 (1992): 173–200.

Daryl, Philippe. Ireland’s Disease; Notes and Impressions. The Author’s English Version. London: George Routledge and Sons, 1888.

“Do We Really Only Live in Three Dimensions?” CERN, February 17, 2012. https://cmsexperiment.web.cern.ch/index.php/physics/do-we-really-live-only-three-dimensions.

Evelyn, John. Sylva, or A Discourse of Forest-Trees. London: John Martyn, 1664.

Ferraz, Marcelo C., ed. Lina Bo Bardi. São Paulo: Instituto Lina Bo Bardi e Pietro M. Bardi, 1993.

Galton, Francis. Inquiries into Human Faculty and Its Development. New York: Macmillan, 1883.

Gillam, Barbara. “Stereopsis and Motion Parallax.” Perception 36, no. 7 (2007): 953–54.

Hall, Edward T. The Dance of Life: The Other Dimension of Time. New York: Anchor Press/Doubleday, 1983.

Hamacher, Duane. “Aboriginal Traditions Describe the Complex motions of Planets, the ‘Wandering Stars’ of the Sky.” The Conversation, August 15, 2018. https://theconversation.com/aboriginal-traditions-describe-the-complex-motions-of-planets-the-wandering-stars-of-the-sky-97938.

Hamacher, Duane, and Krystal De Napoli. “The Rapidly Growing World of Indigenous Astronomy.” Free Astronomy Public Lectures, Swinburne University of Technology, Centre for Astrophysics & Supercomputing, June 1, 2018. Audio recording, 1:08:54. https://australian-podcasts.com/podcast/free-astronomy-public-lectures/the-rapidly-growing-world-of-indigenous-astronomy-.

Havlik, Andrew M., Duncan A. Carmichael, and Julia Simner, “Do Sequence-Space Synaesthetes Have Better Spatial Imagery Skills? Yes, but There Are Individual Differences.” Cognitive Processing ١٦ (٢٠١٥): ٢٤٥–٥٣.

Haynes, Raymond, Roslynn D. Haynes, David Malin, and Richard McGee. Explorers of the Southern Sky: A History of Australian Astronomy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1996.

Janca, Aleksandar, and Clothilde Bullen. “The Aboriginal Concept of Time and Its Mental Health Implications.” Supplement. Australasian Psychiatry 11, no. 1 (2003): S40–S44.

Johnson, Dianne. Night Skies of Aboriginal Australia: A Noctuary. Sydney: Sydney University Press, 2014.

Jonas, Clare N., and Mark C. Price. “Not All Synesthetes Are Alike: Spatial vs. Visual Dimensions of Sequence-Space Synaesthesia.” Frontiers in Psychology 5, no 776 (October 2014). https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2014.01171.

Keegan, Claire. Foster. London: Faber & Faber, 2010.

Lecky, William Edward Hartpole. A History of Ireland in the Eighteenth Century, New Impressions. Vol. I. London: Longmans, 1913.

Lewis, Samuel. Topographical Dictionary of Ireland. London: S. Lewis and Co., 1837.

Manning, Erin. Relationscapes: Movement, Art, Philosophy. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2012.

Massumi, Brian. Parables for the Virtual: Movement, Affect, Sensation. London: Duke University Press, 2002.

McCracken, Eileen. “The Woodlands of Ireland Circa 1600.” Irish Historical Studies 11, no. 44 (September 1959): 271–96.

Minkowski, Hermann. “Space and Time.” In The Principle of Relativity: A Collection of Original Memoirs on the Special and General Theory of Relativity, edited by H. A. Lorentz, A. Einstein, H. Minkowski, and H. Weyl. Translated by W. Perrett and G. B. Jeffery, 73–91. New York: Dover Publications Inc, 1952.

Munn, Nancy. “The Cultural Anthropology of Time: A Critical Essay.” Annual Review of Anthropology 21 (1992): 94–123.

Richard Nairn. “A Brief History of Ireland’s Native Woodlands.” Coillte Nature, October 19, 2020. https://www.coillte.ie/a-brief-history-of-irelands-native-woodlands/.

Neeson, Eoin. “Woodland in History and Culture.” In Nature in Ireland: A Scientific and Cultural History, edited by John Wilson Foster and Helena C. G. Chesney, 133–156. Dublin: Lilliput Press, 1997.

Neimanis, Astrida, and Rachel Loewen Walker. “Weathering: Climate Change and the ‘Thick Time’ of Transcorporeality.” Hypatia: A Journal of Feminist Philosophy 29, no. 3 (Summer 2014): 558–75.

Ní Dhomhnaill, Nuala. Selected Essays, edited by Oona Frawley. Dublin: New Island, 2005.

Ní Dochairtaigh, Kerri. Thin Places. Edinburgh: Canongate Books, 2021.

Norton, John D. “Spacetime.” University of Pittsburgh Department of History and Philosophy of Science, accessed April 14, 2023. https://sites.pitt.edu/~jdnorton/teaching/HPS_0410/chapters/spacetime/index.html.

Ó Cadhla, Stiofán. Civilizing Ireland: Ordnance Survey 1824–1842: Ethnography, Cartography, Translation. Dublin: Irish Academic Press, 2007.

Paterson, T. G. F. Country Cracks; Old Tales from the County of Armagh. Dundalk: W. Tempest, Dundalgan, 1939.

Pilz, Anna, and Andrew Tierney. “Trees, Big House Culture, and the Irish Literary Revival.” New Hibernia Review/Iris Éireannach Nua 19, no. 2 (Samhreadh/Summer 2015): 65–82.

Pluymers, Keith. “Taming the Wilderness in Sixteenth- and Seventeenth-Century Ireland and Virginia.” Environmental History 16, no. 4 (October 2011): 610–32.

Proust, Marcel. In Search of Lost Time, Volume 1, Swann’s Way. Translated by C. K. Scott Moncrieff and Terence Kilmartin. New York: The Modern Library, 1992.

Reid, Bryonie. “‘That Quintessential Repository of Collective Memory’: Identity, Locality and the Townland in Northern Ireland.” In Senses of Place, Senses of Time, edited by Brian Graham and G. J. Ashworth, 47–60. Oxon: Routledge, 2016.

Robinson, Tim. “An Interview with Tim Robinson.” By Brian Dillon. Field Day Review 3 (2007): 32–41.

Robinson, Tim. My Time in Space. Dublin: The Lilliput Press, 2001.

Robinson, Tim. Setting Foot on the Shores of Connemara & Other Writings. Dublin: The Lilliput Press, 1996.

Rouw, Romke, and H. Steven Scholte. “Increased Structural Connectivity in Grapheme-Color Synaesthesia.” Nature Neuroscience 10, no. 6 (June 2007): 792–97.

Rovelli, Carlo. The Order of Time. Translated by Erica Segre and Simon Carnell. London: Allen Lane, 2018.

St Augustine, Confessions. Translated by R. S. Pine-Coffin. Harmondsworth: Penguin Books, 1961.

Simner, Julia. “Defining Synaesthesia.” British Journal of Psychology 103 (2012): 1–15.

Simner, Julia, Neil Mayo, and Mary-Jane Spiller. “A Foundation for Savantism? Visuo-Spatial Synaesthetes Present with Cognitive Benefits.” Cortex 45, no. 10 (November-December 2009): 1246–60.

“Slieve Gullion.” Northern Ireland Place-name Project. Accessed April 3, 2023. https://experience.arcgis.com/experience/9b31e0501b744154b4584b1dce1f859b/page /Place-Name-Info/?data_id=dataSource_1-PlaceNames_Gazeteer_No_Global_IDs_3734%3A23950.

“Studying Truth with Wolfgang Tillmans.” Tate Museum. Accessed April 10, 2023. http://tate-tillmans.s3-website.eu-west-2.amazonaws.com/.

Tate Modern. “Wolfgang Tillmans: 2017.” Press release. Accessed April 10, 2023. https://artblart.com/tag/wolfgang-tillmans-truth-study-center/.

Till, Jeremy. “Thick Time: Architecture and the Traces of Time.” In Intersections: Architectural Histories and Critical Theories. Edited by Iain Borden and Jane Rendell, 283–95. London: Routledge, 2000.

Viereck, George Sylvester. “What Life Means to Einstein: An Interview by George Sylvester Viereck.” The Saturday Evening Post, October 26, 1929.

“Winter Solstice – Setting Sun Illuminates Slieve Gullion Passage Tomb.” Ring of Gullion, December 25, 2012. https://ringofgullion.org/news/winter-solstice-setting-sun-illuminates-slieve-gullion-passage-tomb/.

“Wolfgang Tillmans, Truth Study Center, Tate 2017.” Tate Modern, April 2018. https://www.tate.org.uk/art/artworks/tillmans-truth-study-center-tate-t15603.