Broken Stories of the Supernatural

This essay is about when time splinters and breaks under the pressure of the supernatural. It suggests that the stolen moments in which people experience the divine, the demonic and the otherworldly provide us with important conceptual and methodological tools with which to think about -- to think with -- stories of the supernatural. I use historical sources, personal (re)collections and glitch theory to argue that, in the end, the structure and significance of supernatural experiences are not revealed in linear narrative but in their brokenness.

Key Words:

supernatural, glitch, time, philosophy of history, narrative

Kristof Smeyers,

Ruusbroec Institute, University of Antwerp

1. Untimeliness

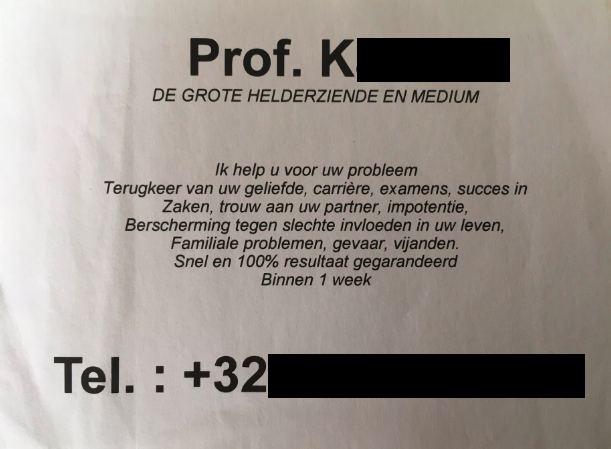

On my desk: a pandemic-sized pile of crumpled business cards and DIY adverts. They come in all sizes, are printed on different kinds of cheap paper in a dazzling range of fonts – sometimes on the same small card – and many are written in a melange of languages. The text on the faded card on top of the pile crams Dutch, French, English, and Spanish into one breathless sentence. The card offers a wide range of specific services. It promises quick-fix solutions to any problem you may have, mundane or magical. And it uses plenty of exclamation marks to convince you of the supernatural skills of “Professor Docteur Jean-Michel.” The ad appeals to an assumed desperation in its recipients, but its tone suggests a desperate “professor docteur,” too. It is simultaneously a remedy and a symptom.

In March 2020, I stopped throwing away these cards each time one arrived in my post box (which over the past few years has been often). Without any clear purpose, I began to keep them in my office. Some function as bookmarks in historical studies of shapeshifters, urban necromancers, UFOs; they stick out of books on the myths of disenchantment, the alleged decline of magic, the birth of modernity: the books that underpin my work as historian of religion and the supernatural. Inadvertently this collection has grown into an unofficial Yellow Pages of the twenty-first-century magical marketplace of the city of Antwerp. And, at first unthinkingly, I have put these ads into contact with (literally: touching, lying on top of, pushed between bits of) their own past, like some sort of feedback loop between now and then.

The thing is: My research has since then begun to fray at the edges, or rather, my subjects have started to chew away at it, defying any linearity and pushing back against my discipline. Multiple acts of transgression – temporal feedback loops, glitches – have been taking place at my desk since March 2020. Some, like bringing modern-day business cards into a historical environment, are of my own doing. Others cause disruptive interference from within the records themselves. A diary fragment from 1834: “They took me I don’t know where, and next I know I have a beard o’ days, but I feel as like I’ve only been gone a moment!” Another entry in a different diary, from 1902: “And sure enough the little joker appears in their bedroom and pounds and punches them until he has them demented with fear. Then disappears just as mysteriously as he came…This is the queer thing…He never left his house.”[1] From Reddit, posted in 2021: “‘[A]round 10:00 I go lock the front and back door…at about 12:00…I see the back door unlocked and open…I make sure the basement door is latched and I go back upstairs after making sure the back door is locked as well. At about 2:00…once again I see the back door wide open, so is the basement door. I just close the door…and lock it as hard and as fast as I can. I go upstairs and I did not sleep for the rest of the night.” Later, watching the footage of that night on the home camera security system, time jolts strangely backwards and forwards, much like the doors in the house keep opening seemingly by themselves.

How do you study a past – and a present – inhabited by people for whom the linear experience of their own lives was suddenly, sometimes violently, disrupted by the supernatural, and for whom time and place momentarily collapsed in on themselves? “They” in 1834 are fairies; they abduct people and, doing so, pull someone out of their own time stream, “away with the fairies” for a while – whatever a while can be. The “little joker” in 1902 is a malevolent entity nicknamed “Petie,” bilocating to terrorise people in their homes, shimmering in and out of existence at will. Folkloric beasts, flickering ghosts, and faltering aliens can all cause such glitches: in how people sometimes perceive time, their own bodies, and their surroundings as out of joint or out of place. These glitch encounters are cognitively jarring for the people who experienced them, and they should be jarring for anyone who tries to write with the experience rather than analyse it away. This point, and the perspective of glitch and fracture, can be extended to other histories, of disruption, dislocation, trauma: histories in which individuals or groups were also ripped out of their own timelines by forces outside of their control. Kodwo Eshun, for example, writes evocatively about slavery and the Afrodiaspora in terms of temporal disjunction and displacement when he rethinks “the idea of slavery” as an alien abduction: “[W]e’ve all been living in an alien-nation since the eighteenth century.”[2] Supernatural histories especially attune us to the potential of the glitch as starting point for historical inquiry; they even offer a (metaphorical) way into attempts to capture the experience and consequence of the slave trade.

But to begin with the glitch also means to unsettle my own practice. My starting point is Katharine Hodgkin’s phrase about the study of witchcraft as “a place where history asks questions about itself.”[3] Simply put, supernatural glitch accounts and business cards from an enchanted economy have put me in a place where I cannot but ask questions about myself, my praxis, and my conception of historical time. The pile on my desk has become a methodological inflection point, inflicting itself quite literally, quite physically, on my research. Witch doctors and palm readers with email addresses and WhatsApp reach out to me – interrupt me – from between pages that hold their colleagues and predecessors from previous centuries. History’s “questions about itself” when faced with glitches are about language, representation, and narrative truth. Perhaps just as fundamental, they are about the practices of the historian: collating, selecting, curating, collecting, dismissing, narrating, explaining. And, crucially for me, they are about change over time and changes in time. These last two categories especially interrogate how we can denaturalise the psychopathological and historicising perspectives that many sources for supernatural histories embody. Witchcraft, and by extension encounters with what I will call “supernatural glitches,” put these questions centre stage because they confront us with the limits of linear approaches, and of historical methods more generally.

Can we reconstruct people’s supernatural glitch accounts in historically meaningful ways? What does that mean? And how, if at all, can we do so without writing those accounts into histories that force a linearity onto moments that actively resist it – histories that would remove the glitch from the experience? These questions matter because people in the past and present often describe their encounters with the supernatural as not fitting and profoundly disruptive in their individual lives: beards that grow in mere minutes; a gnome-like creature that causes havoc in two places at once; doors that unlock and open in the stolen moments of a security camera recording. Such encounters break the linear conception of one’s own timeline, sometimes momentarily, sometimes lastingly.

These questions matter also because a mainstream conception of history continues to relegate encounters with the supernatural to the dustbin of an irrational past, an ill-defined and imaginary dark age. The supernatural does not belong in this conception, even if professional historians have criticised it for nearly half a century now, especially since the publication of Keith Thomas’ foundational study of early modern England, Religion and the Decline of Magic, in 1971. Every manifestation then merely serves as a spectacular anachronism that underpins the validity of the disenchantment paradigm (or myth) in societies that build themselves on the idea of rational modernity.[4]

Here, then, is a double non-belonging or untimeliness that needs unpicking: in the life of the individual who experienced a supernatural glitch, and in popular understandings of history as trajectory towards rationality. How to do justice to the former, even to put the glitchiness of supernatural encounters central to our inquiries, and not reinforce the Weberian narratives that run like a current underneath the latter, which paint such encounters as incompatible with modern society and history as time’s arrow moving relentlessly forward?[5] How do we keep the strange and broken character of glitch accounts intact when trying to make sense of them? Glitch histories disrupt what historians do in fundamental, outright scary ways.

Here, also, manifests a tension between historicism – understood in this instance as the power of condemning something undesirable to the past; the dustbin – and the timeless impression that so many supernatural experiences make on us. Whether in 1834, 1902, or 2021, time and again, accounts of glitch encounters follow along similar narrative beats even if their internal mechanisms are often dissimilar. The repetitive and referential nature of glitch anecdotes in the past and present can make them appear as a massive, shapeless, hypnotic corpus. They become a hypertext in which deeply personal stories of the extraordinary shed their spatial and chronological coordinates, their situatedness. If, for example, the account of a fairy abduction in the early nineteenth century reads familiar to modern eyes, it may be because strikingly similarly worded testimonies exist of twentieth- and twenty-first-century alien abductions: They emphasise time jumps, temporal amnesia, blackouts (as well as sexual violation). Such stories then become part of something else entirely, something ahistorical and separate from ourselves, something that oscillates between past and present but no longer belongs to either, much like the pile of business cards from an enchanted underground economy on my desk.[6] How to reconcile their individual situatedness and the contextual sense of rupture they all share? How, in other words, to think historically about the palimpsestic nature of all those different lived temporalities that intersect with the supernatural, and that are so densely layered in meaning not least because they influence and shape each other, often across time?[7]

The two tensions, of (individual, historical) non-belonging and (social, cultural, historical) context, are crucial if we are to come to grips with the brokenness that permeates personal histories of the supernatural without attempting to “fix” them, and without making too much sense of them. These tensions circle around the figure of the historian who curates, interferes, misplaces, destroys, and makes haphazard piles to create a narrative – a chronological sequence – that, because of its linearity, itself becomes an anomalous glitch of sorts.

So we set out to break the timeline.

2. End time

“Prof. K., the great clairvoyant and medium. I help you with your problem: return of a loved one, career, exams, business success, fidelity, impotence, protection against bad influences, family issues, danger, enemies. Fast and 100% guarantee of result within 1 week.”[8]

The business cards on my desk are quaint, out-of-time-looking – not because of their content but because of their materiality. Scraps of paper, objets trouvés, relics of a bygone age. They attest to the kind of supernatural underground economy I usually read about in histories of nineteenth-century Europe. Cunning-folk, wizards, exorcists, fortune-tellers, people accused of witchcraft, unwitchers, palm readers, shamans, demon tamers: They were the entrepreneurs that operated on the margins of industrialisation and urban expansion; now they operate on the margins of a globalised service economy. I have seen adverts just like the ones in the pile, in archives, dating from over a century ago. But by and large, this economy has moved online, tapping into new markets: a migration accelerated by Covid-19. Acts of occultism and ritual magic have also gone digital. Djinns arrive by courier at your doorstep from eBay depots; trans-Atlantic covens take place on Zoom; self-styled sorcerers broadcast live on YouTube to place curses on capitalism and big pharma; WitchTok brings New Age spirituality and warped ideas about historical witchcraft to new generations.

In 2020 thousands of people caused ‘manifesting’ (asking favours of the universe) and ‘shifting’ (sending your conscience temporarily to another reality) to trend on TikTok. Banking on the perception of a worldly disenchantment, these deliberate and recorded glitch manifestations present themselves as alternatives to, even critiques of, a materialist mainstream, and they do so in profoundly materialist ways. Enchantment has always benefitted from technological developments, from print press to virtual reality.[9] The Sunday Times announced ‘manifesting’ the buzzword of 2021 and explained its popularity, in journalistic hyperbole, as a reflection of “the peak of anxiety about world collapse.”[10] The supernatural thrives in apocalyptic settings. The cards on my desk, much like their predecessors from earlier centuries, use a language of magical anchorage and solace while painting a picture of a world in disarray, confusion, alienation. They speak of the end times, Judgement Day, and the Millennium. They haunt me (/hound me) in my writing.

Hauntology can be described (too) succinctly as an ontology with a ghost ‘h’ that differentiates between being and presence. Or it can be summarised as “to be is to be haunted” – not necessarily just by a past that manifests in the present.[11] Derrida developed his hauntology in part as a reaction to the popular understanding of Francis Fukuyama’s argument about the victory of liberal democracy as the end of history.[12] (And, more implicitly, hauntology responded to the turmoil in the immediate aftermath of the collapse of the Soviet Union.) Haunting has always been political. Mark Fisher refitted Derrida’s hauntology to describe the folk horror cultural products that flooded the British market in the 1970s, but also to place that popularity against a backdrop of Thatcher’s ideological war on cultural spaces that resisted or escaped market-driven neoliberalism.[13] Hauntology popped up again in critical theory after the financial crisis of 2008.

History does not move like a straight arrow from one point to another all the way to an endpoint. Derrida blurs past and present into a spectral whole that negates the notion of a historical end and replaces it with a loop. But even if Fukuyama’s argument about the end of history has often been reduced to a catchphrase deserving of mockery, the sense that civilisation or history has ended or was hurtling towards the curtain call is a recurring flex in historiography, and in cultural criticism more broadly, as well as on homemade business cards. The early twentieth-century historian Marc Bloch wrote poignantly about the eschatological nature of historical practice in Europe, and about historians’ incapacity to escape linear structures of temporality and meaning.[14] As a historian of the Middle Ages writing during the Second World War, Bloch was well aware of the European proclivity to apocalyptic language. This is a language that has its inflection in a corpus of modern analyses of the dire state of the West, most famously in Oswald Spengler’s Der Untergang des Abendlandes,[15] published after the First World War at a moment in time when many people in Europe had close encounters with the mystical and the supernatural.

Spengler ostentatiously rejected linear understandings of a world history landmarked by major chronological turning points: history conceptualised as global timeline. Instead he imagined history as an ebb and flood of self-sustaining, ultimately doomed cultures. Surrounded by destruction and grief, Spengler observed the winter of Western culture. (Seasons move slowly, if still teleologically, in such big histories. In his magnum opus, Spengler’s contemporary, the Dutch historian Johan Huizinga, wrote of the later Middle Ages as an “autumn-tide.”[16]) Not a singular arrow, then, but waves crashing onto a beach: a natural progression of time just the same. Besides, historians never had the monopoly on eschatological moods. Some adverts from the underground economy then and now describe this world as staring down the precipice of total annihilation. From atop the pile of business cards Professor Docteur Jean-Michel announces the imminent apocalypse. The end times are upon us, and supernatural salvation is the best we can hope for. Fortunately for us, it comes cheap.

3. Glitch experience

Howling at distance, ocean

pulling between us, bending time

(Anne Michaels, “Three weeks”)

While business cards from the underground economy accumulated on my desk, and while researching nineteenth-century supernatural phenomena, I began to search online for recent accounts of glitch experiences. I was not alone. As early as June 2020, the digital consumer research company Brandwatch pointed out that people were, since March, increasingly going online to read accounts of bizarre encounters on messaging boards and social media.[17] They are everywhere: a pandemic paranormality in which people share, discuss, and reach out to others; a living, global archive.

Spectral apparitions in particular abounded as people spent their days inside, looked around, and listened to the unfamiliar sounds of their familiar surroundings. (Around the same time, the American ghost researcher John E. L. Tenney suggested in the New York Times that the noise of expanding floorboards and old pipes explained each instance of “spectral roommates.”[18]) Perhaps an increased awareness of self, aided by society momentarily slowing down, does lift the veil between worlds. “Haunted places are the only ones where people can live,” Michel de Certeau wrote riffing on Derrida’s hauntology.[19] Even if all human places are haunted, as de Certeau argues, the pandemic-induced sudden awareness of a haunted home caused glitches around the world. In this abundance of anomaly experiences, fractures showed; supernature was healing.

The countless stories online repeat and share a sense of temporal dislocation. Encounters with ghosts at home, but also with cryptozoological and extraterrestrial creatures on ever-longer pandemic walks, and experiences of deepened, ecstatic, sometimes theophanic spirituality – all increasingly recorded since March 2020 – mess with people’s already fraught sense of time. The use of tenses in accounts reflects this. They shift fluidly, and at first unnoticed, between past and present. Someone “saw” a ghost that “moves” through a wardrobe; someone “feels” a presence that “had been” nearby. As such these accounts defy the curatorship of historians and ethnographers: They resist the structure of timelines and narrative arcs. (‘You know who had an arc?’ Paulie Walnuts, not incidentally the most supernaturally attuned character in The Sopranos, quips: ‘Noah.’)[20] Temporal dislocation and anti-linearity are defining traits of many supernatural glitch experiences.

And yet linear time is, often by necessity or lack of viable alternative, the lens through which we look at the world and its history – and at (hi)stories of the supernatural, in which case linearity has traditionally served very well to consign these subjects and beliefs to a faraway history, to a past perfect tense. In this version of history supernatural experiences are treated not so much as glitches in people’s lives but as anachronistic hiccups on a grand timeline. Temporality, then, poses a challenge to anyone dealing with a supernatural glitch encounter, whether one’s own or someone else’s. This challenge, too, manifests in tenses: Do we write about glitches in a historical past or an ethnographic present? After all, what Anna Lowenhaupt Tsing has argued about the language of ethnographic writing, that it ties “to a conceptualization of culture as a coherent and persistent whole,” also goes for the past tense in which history is predominantly written. Both can create “a timeless scene of action” and put the subjects of our writing outside the “time of civilized history.”[21] Remember, neither a “coherent and persistent whole” nor a “timeless scene of action” are desirable outcomes when writing histories of the supernatural. They are broken, not whole, and they are untimely, not timeless.

Reading many accounts in succession – whether online, in the archive or, like me, moving between all kinds of repositories of glitch experiences – brings to the surface what Giorgio Agamben calls “pure historical essence”: their relation to time. Talking about toys, Agamben touches on a central nerve that also twitches under the skin of supernatural histories. “[D]ismembering and distorting the past or miniaturizing the present – playing as much on diachrony as on synchrony –,” he writes, “makes present and renders tangible human temporality in itself, the pure differential margin between the ‘once’ and the ‘no longer.’”[22] To approach glitch experiences merely as “alternative temporalities” brings into focus the “differential margin” in which glitches (and, in Agamben’s theory, history as a whole) happen. Recognising this necessarily has repercussions in how supernatural histories must be written. Perhaps we should follow suit with the sources and try to recreate their sense of temporal confusion. To break these histories perhaps we should play with tenses in our writing, like children play with dice in Heraclitus’ depiction of time: not simply acknowledging the dyschronia, the broken-time, in glitch experiences, but making it integral to historical methodologies.

*

It is tempting to collate past and present glitch encounters with the supernatural into a historical timeline on which certain phenomena replace others as time wears on. Think again of the nineteenth-century telling of an abduction by fairies and compare it to more recent accounts of abductions by aliens. In both types of encounter, accounts often mention a glitch or a lapse in time, moments that are lost, unaccounted for. This could make the glitch experience appear as timeless, or more precisely, of all times. We could observe a phenomenon through the centuries, only the outward appearance changes. Aliens replace fairies; UFOs replace religious visions. Simple.

By extension, we could then even discern templates of glitch experiences throughout history. Extraordinary bodily phenomena of mysticism such as ecstasies, stigmata, and long periods of fasting, for example, have occurred throughout the history of religions in ways that can suggest a continuum, not least because mystics themselves have often linked their bodies to those of illustrious, saintly predecessors, drawing up supernatural lineages. In turn, historians have studied phenomena in terms of historical (chronological, geographical) waves and trends. But however useful and illuminating, such approaches plaster over the temporal cracks and connections that show on an individual scale. The specificity of time matters; linearity can break; a moment can become a transhistorical portal. What exactly happens at three o’clock on a Friday afternoon in 1916, for instance, when a young woman in Leeds sinks into a trancelike state and the wounds of the Crucifixion appear on her hands and feet? In her diaries, she details her synchronised suffering with Christ as he is nailed to the cross almost 2000 years earlier. In her experience, she is with him in body. But the stigmata experience also splits her temporally: She is at once on Calvary and offering her supernatural wounds as a sublimation for the death and pain of the First World War.[23] This temporal dissonance is crucial to understand her stigmatic experience as glitch, and her personal timeline as broken.

Injecting some kind of (linear!) continuity into a hypertext of glitch experiences therefore also stems from thinking historically, and from understanding phenomena to progress from within a constantly shifting cultural context. Seen from that perspective, aliens have replaced fairies because technologies and frames of reference have changed. Again: Simple. The temptation to compare, even equate, supernatural glitches across periods and cultures is rooted to some extent in the unified field theory as ufologists reconceptualised it in the 1960s to bring together poltergeists, fairy changelings, and extraterrestrial lifeforms in a melting pot of folklore, religion, and the paranormal. Within this unified field, glitch experiences are labelled, then categorised in the same superstructure of phenomena. As such they offer a compelling cross-cultural view of the variety of human experience. But they also create the impression of an ahistorical whole out of very personal, intimate stories that are primarily found in scattered fragments and, perhaps more crucially, in gaps between fragments. Those individual stories can riff off each other, even accumulate meaning when put together. But they remain anomalous experiences, meaningful in a first instance for the individuals to whom they happened.

Looking at the cards on my desk, I realise the pile is also an effort to create a whole out of fragments, and at bringing the cards into histories of the supernatural. Diachronic attempts at labelling the supernatural tend to obscure, rather than clarify. Phenomena are mislabelled, interpreted wrongly, ascribed different root causes, and lumped together because they appear outwardly similar, especially when taken out of their context. This can happen in spite of good intentions to provide a deeper understanding of glitch experiences. Since its conception in 1882, for example, the British Society for Psychical Research has categorised historical and contemporaneous personal experiences of stigmata together with fairy sightings, crop circles, and all sorts of precognitive capabilities as “spontaneous phenomena,” a subcategory of “paranormal abilities of the living.”[24] They, too, in a structured research catalogue, form a hypertext that is timeless, by which I mean they appear not as “un-timely” but rather as “of all times,” transcending the specificity of the context in which an individual encounter happened.

I think such classifications have had an unintended opposite effect in the academy. They have entered many historians’ frames of mind, for instance, to form an ambiguous supernatural comprising everything that invokes “a spooky sense that there was more to the world.”[25] These attempts to find meaning in glitch experiences – to historicise and classify them, to make them part of a symbolic universe – have, in fact, rendered those experiences meaningless; paradoxically, by structuring them into categories they have been forced into a shape that “we cannot fully identify,” and in which the strangeness and singularity of an experience have become lost or, worse, irrelevant.[26]

Perhaps worse than obfuscation is extraction. Faced with my small collection of supernatural scrap paper, Agamben shakes his head: The collector of artefacts “extracts the object from its diachronic distance or its synchronic proximity and gathers it into the remote adjacenc[y] of history.”[27] What does this extracted collection do? It mixes with my work in a physical sense: cards appear unasked for between my notes or in a book; they glitch up my workspace. And it repurposes a group of objects, re-engineering them to be part of a history, perhaps prematurely. Am I not building my own arc here? Every now and then I resort to rearranging the business cards. Some get lost; some I find again by accident. Increasingly, they scatter around the room. The countless online accounts of glitch encounters also fracture metaphors of history as forward arrow much like similar stories from the past disrupt a sense of linearity, to the point that it becomes unclear who experienced what when, or rather, who impinged on whose sense of time: the ghost/alien/creature, or the person seeing them, or the historian with their hindsight. Such organic confusions and broken narrative rhythms mark cracks in the notion of personal or lived experience.

That is problematic for cultural historians like me. First, because of our longstanding emphasis on the event in cultural historical method. We make use of moments of crisis or exception – a cat massacre,[28] a wave of UFO sightings – to delineate the imaginative universe of historical actors within a broader context. So much effort goes into finding meaning through contextualisation, into stitching the peculiar – the stand-out event – into a fabric in which it can make sense. Second, it is problematic because of cultural historians’ relatively recent focus on lived experience, inspired by the work of anthropologists like Clifford Geertz and Bronislaw Malinowski.[29] (This shift has unsurprisingly also led to more reflexivity towards historians’ own practices.) The focus on lived experience pervades research of the supernatural especially, although what is meant by it is usually left suitably vague, and does not seem to include the intense glitchiness that permeates personal records.[30] To take seriously lived glitch experiences of people in the past and now means to give space to the sense of temporal disruption and profound un-context of the supernatural as people have described it time and again. It means to acknowledge how time shapes and distorts accounts of glitch experiences.

After all, time functions as distance, too. It mediates the disruption and directness of glitch encounters for those who experienced it, both in the form of a length of time that passes before the experience is put into words and in the form of how time works in accounts. The pure experience, defined as a revelation, something immediate, becomes inaccessible because time interferes (and also, as mentioned, because through language it enters a referential structure existing in connection to countless other glitch stories). Time creates distance also for the historian of those encounters, in obvious and less obvious ways. History, Agamben writes, “must, like every human science, renounce the illusion of having its object directly in realia, and instead figure its object in terms of signifying relations.” Those relations are between two ‘correlated and opposed orders’: diachrony (event) and synchrony (structure), neither of which, Agamben argues, exists in their pure form. History happens instead precisely in the differential margin between the two, in the tension of distance.[31] Any attempt to bridge that distance is ultimately doomed.

Warning signs abound, then, when writing the broken histories of the supernatural. The historian and critic Hayden White has pointed out how “narrative prose discourse that purports to be a model, or icon, of past structures and processes in the interest of explaining what they were” often ends up representing those very structures.[32] We cannot disavow linearity altogether if we want to write with the magic of glitch encounters rather than analyse it away, but we can be more explicitly aware of our own position in the glitch narrative.

In The Rings of Saturn W. G. Sebald writes about the illusions and misplaced confidence of history: “We, the survivors, see everything from above, see everything at once. And still we do not know how it was.”[33] We must try to un-see everything at once if we are to begin to know “how it was” – and is. Patterns and loops still emerge but each particle, each individual experience is time-bound, haunted by its own fractured Zeitgeist. On my wall, above the pile of cards from the underground economy, hangs a fragment of a T. S. Eliot poem that, as I read it again, only emphasises the idea of some sort of feedback loop in my praxis: “We shall not cease from exploration / And the end of our exploring / Will be to arrive where we started / And know the place for the first time.”[34]

Does temporal confusion inevitably lead to historical illegibility? It gets dark.

I look up from my desk when Antwerp’s cathedral tower lights up outside my window: a pale LED flare, an early modern church for the future wrapped in scaffolding. I must have lost track of time.

4. Breakpoints

The man who was away with the fairies in 1834 experienced time out of joint. But where did he go?

Landscapes are “cluttered with the detritus of past living,” Joyce Appleby writes,[35] glitch encounters can happen anywhere. They necessarily take place somewhere. Michel de Certeau’s phrase, that the only places people can live are haunted, can be inverted. “We talk of ghosts as if they can only be people,” Christopher Josiffe, the librarian of the haunted Senate House in London, writes.[36] Places can behave in ghostly ways, too. They are not simply inhabited by glitches; they are themselves glitches, their “dimensions changed,” their “purpose erased.” Time behaves differently there. “There seem to be corridors that remember being drawing rooms,” Josiffe continues, “attics that remember being bedrooms.”[37] Put differently: Where did the fairies take the man for time to go weird, or where was he for the glitch event to become possible?

In the 1980s the meridian between the eastern and western hemispheres was moved 102 metres to the east. In Greenwich Park in London, at the Royal Observatory, the visible line in the grass that has been there since 1851 became in effect defunct as it was replaced by an invisible, more accurate meridian line. Ever since, glitches occur in the park, messing with people’s time. A park keeper “jumps” instantly from one side of a hill to the other. Students on a trip get lost “for days” – or is it only an hour? People find themselves suddenly having walked into an empty woodland area bereft of sunlight and wander seemingly forever.[38] Clearly, the where of the glitch matters, time does not behave the same everywhere. Some places stretch it out or compress it more than others.

One way to think historically of narrative glitches – or glitch narratives – is in spatial terms. In the way Edward Soja conceptualises “thirdspaces” as uncanny irruptions in which the boundaries between material reality and the imaginary collapse, spaces that are simultaneously “of the moment and historical.”[39] But perhaps more so in the way the anthropologist Marc Augé writes of “non-spaces” (non-lieux). Augé argues that the last few decades have been witness to a decline in anthropological place, a “concrete and symbolic construction… which serves as a reference for all those it assigns to a position.”[40] It has been replaced by indifferent “supermodern” spaces, overloaded with an excess of time, such as hotel lobbies, supermarkets, airport lounges – one could add, as Roger Luckhurst does, corridors to this uncanny topography or, in Esme Partridge’s analysis, business districts that die after offices close in the evening.[41] Augé touches briefly on how time works differently in non-places. These are, incidentally, also the kinds of contemporary spaces where glitches manifest: not indifferent per se, but unsettling in their supermodernity. Supernatural glitch encounters happen in – and create, and supercharge – places that are “like palimpsests on which the scrambled game of identity and relations is ceaselessly written.”[42]

Supernatural non-places can be physical locations, deep in the woods, behind a dumpster, on a historian’s desk, or they can be metaphysical. What they have in common is that they are all places of temporal friction, and they are manifold. They have many human experiences from different times folded into them. All places are palimpsests of history. But what sets supernatural non-places apart is just how jumbled those layers – of memory and possibility, of past and future – can be: There is an excess of time. Time is compressed, stretched, superimposed on itself like a Victorian spirit photograph, or made to feel absent altogether.

Starting research from the place of the glitch, then, leads at once into different directions. For Augé these directions are opposites, leading either to place as “never completely erased” or non-place as “never totally completed.”[43] He writes about the “spatial vertigo” in non-spaces of supermodernity – “as though we ourselves were about to lose our bearings in time and emerge somewhere else entirely” – mostly in metaphorical terms.[44] Accounts of glitch encounters bring such feelings into a lived, embodied reality. People’s physical bodies disappear for a while and suddenly reappear somewhere else; some hours feel like days, or days like hours, in a very real, embodied sense and not just as hyperbole or platitude (Time flies when you’re having fun!). Like Derrida’s hauntology, Augé’s non-spaces were a reaction against the end of history, crystallised into an image of a globalised world in which space was homogenous and flat. Seen from that perspective, supernatural non-spaces defy that image: They are particular, not generic; not flat, but sometimes so deep that people fall and keep falling. In 2014 staff at Greenwich Park found a phone attached to a selfie stick. The last photo on the phone allegedly shows the disappeared owner of the phone against a deeply disturbing background.[45]

Are non-places where individual end times happen, like in Greenwich Park? Do they always mark a definitive turning point in people’s lives? Or do people, sometimes deliberately, visit the glitch only briefly and get out, to resume as before? I assumed, wrongly, that people dwelt in these places long after the initial experience and that people haunted by them returned to haunt them, perhaps never fully left them at all. That the glitch, the supernatural disruption, comes to define the rest of someone’s life and casts everything else into a different, shady light. The cultural critic William Irwin Thompson also points to the spectacular and disruptive, the “exaggeration of the archetypal encounter,” not a sustained sense of spirituality, as the defining event in religious meaning-making.[46] But glitch encounters, no matter how disruptive and spectacular, can move into the periphery of life; the supernatural non-place shimmers out of existence. People forget, or get used to it.

Neighbours in Leeds who saw the young woman next door entering into ecstatic states and bearing the Wounds of Christ on her body during the First World War initially corresponded about the experience in terms of mystical glitchiness. They lost track of time when they stayed in the woman’s bedroom for hours. Some described how they were “moved elsewhere… in spirit… our bodies had stayed behind,” as if the ecstasy had caused the room and its contents to be transported to a different plane where time slowed down. Afterwards, witnesses expressed a deep sense of confusion about how long they had been “gone.”[47] Three years later, however, and those neighbours had gotten used to the woman’s regular ecstasies and stigmata. They still visited her, but they no longer shared in the glitch experience. They became spectators instead of participants. They had moved on.

*

Returning one last time to Agamben, stating what may now, in the context of glitch encounters, sound obvious: “History, therefore, cannot be the continuous progress… through linear time, but in its essence is hiatus, discontinuity, epochē.”[48] This essay has tried to offer some ways to begin to convey Agamben’s observation onto the page – and fold it into the historian’s craft, which is always collage and curation, always synchrony and diachrony. Perhaps no place is more of a non-place than the archive. Every voice we encounter there is a revenant, someone summoned back to life into a different time, briefly. But historians dwell in similar ways in the past, too, moving through time in non-linear ways, glitching gloveless into the past. It’s a two-way transgression, and it forms a feedback loop of past and present.

Having picked some arbitrary examples from across the last two centuries, I do not want to suggest that glitch experiences are the same – or even similar in categorical ways – regardless of when or where they happened, or that there is something like a universal glitch experience. The examples instead illustrate how time is something that can be experienced in profoundly different ways, also as non-linear, and as associative. It has implications for how the humanities, and historians especially, think of time as not (always) linear but as something that can reverse, fork, buckle, break. This understanding is necessary to acknowledge the historicity of the supernatural without naturalising its manifestations, to write about glitch encounters as problematic, difficult, and broken. Seen this way, the adverts from the underground economy on my desk are similarly difficult: They exist both within and outside their own time. There is nothing ahistorical about the adverts, but they can be glitches nonetheless. Like glitch experiences, they exist in friction with their context: not archaic, not timeless, but untimely and powerful, because they have the capacity to break persisting paradigms of disenchantment, reason, linearity.

And they have the capacity to disrupt how we understand histories of the supernatural and appreciate their fractured nature. The glitch alerts us to the availability of alternative temporalities with which to tell, write, make history. It can even offer a toolkit with which to recalibrate our historical knowledge more generally. Ruptures haunt us, and they show the value of looking at sightings, visions, apparitions, metamorphoses as glitches that help decentre and denaturalise the trajectory of history. Even while still staggering from the spatial vertigo and temporal whiplash that glitch encounters cause, we continue to reach out to the supernatural to bridge all kinds of distance, in language, between moments, between people, within ourselves. What we find ultimately remains fragmentary and incomprehensible. The structure and significance of supernatural experiences are not revealed in linear narrative but in their brokenness.

That needn’t be a problem.

Breaking a history can be like breaking open an egg. Something is set free.

Note from the editors: in the PDF, the text naming Professor Docteur Jean-Michel imitates the different fonts visible in the calling card.

All pictures by the author.

[1] Both anecdotes come from the Irish folklore database, Bailiúchán na Scol [The Schools Collection], duchas.ie.

[2] Kodwo Eshun, More Brilliant than the Sun: Adventures in Sonic Fiction (London: Quartet Books, 1998), 192.

[3] Katharine Hodgkin, “Historians and Witches,” History Workshop Journal 45 (Spring 1998), 272.

[4] Jason Ã. Josephson-Storm, The Myth of Disenchantment: Magic, Modernity, and the Birth of the Human Sciences (Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 2017).

[5] Such narratives are predominantly based on a misreading of Max Weber’s much-quoted phrase “die Entzauberung der Welt,” Wissenschaft als Beruf (1917).

[6] Sudhir Alladi Venkatesh, Off the Books: The Underground Economy of the Urban Poor (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2006).

[7] Hayden White, Metahistory: The Historical Imagination in Nineteenth-Century Europe (Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1973), especially the introduction.

[8] Translated by the author.

[9] Owen Davies, Grimoires: A History of Magic Books (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2009).

[10] Helen Rumblebow, ‘“Manifesting”: it’s the buzzword of 2021’, Sunday Times, 27 September 2021.

[11] Jacques Derrida, Spectres de Marx: l’état de la dette, le travail du deuil et la nouvelle Internationale (Paris: Editions Galilée, 1993), see also Shauni De Gussem’s essay “On haunting” in the previous issue of Passage (2021).

[12] Francis Fukuyama, The End of History and the Last Man (New York: Free Press, 1992).

[13] Mark Fisher, The Weird and the Eerie (London: Repeater, 2016).

[14] Marc Bloch, The Historian’s Craft, trans. Peter Putnam (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1992). 4, 25-6.

[15] Oswald Spengler, Der Untergang des Abendlandes, 2 vols. (Munich: Oscar Beck, 1918–1922).

[16] Johan Huizinga, Herfsttij der middeleeuwen. Studie over levens- en gedachtenvormen der veertiende en vijftiende eeuw in Frankrijk en de Nederlanden (1919, repr. Leiden: Leiden University Press, 2019).

[17] Covid-19 Daily Bulletin, Brandwatch, 11 June 2020. https://www.brandwatch.com/email/covid19-bulletin-056-11-06-2020/

[18] Molly Fitzpatrick, ‘Quarantining With a Ghost? It’s Scary’, New York Times, 14 May 2020.

[19] Michel de Certeau, The Practice of Everyday Life, trans. Steven Rendall (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1984), 108.

[20] ‘The Legend of Tennessee Moltisanti’, The Sopranos, created by David Chase, season 1, episode 8, HBO, 1999.

[21] Anna Lowenhaupt Tsing, In the Realm of the Diamond Queen: Marginality in an Out-of-Way Place (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2006), xiv.

[22] Giorgio Agamben, Infancy and History: On the Destruction of Experience, trans. Liz Heron (London and New York: Verso, 1993), 70-71 and the essay ‘Time and history: critique of the instant and the continuum’.

[23] N. B.’s manuscript diaries were given to the Jesuit scholar of the supernatural, Herbert Thurston. London, Archives in Britain of the Societas Iesu, 39.3.3.

[24] Anonymous, ‘Note on the visions of Anna K. Emmerich’ in ‘Part 1: Paranormal Abilities of the Living’, Research Catalogue of the Society for Psychical Research 1884–2011. https://www.spr.ac.uk/1-spontaneous-phenomena

[25] Nicola Bown, Carolyn Burdett, and Pamela Thurschwell, introduction to The Victorian Supernatural, eds. Nicola Bown, Carolyn Burdett, and Pamela Thurschwell (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2004), 1.

[26] Marc Augé, Non-Spaces: An Introduction to Supermodernity, trans. John Howe (London and New York: Verso, 2008), 27; Steven Connor, afterword to The Victorian Supernatural, eds. Nicola Bown, Carolyn Burdett, and Pamela Thurschwell (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2004), 274.

[27] Agamben, 72.

[28] Robert Darnton, The Great Cat Massacre and Other Episodes in French History (New York: Basic Books, 1984)..

[29] Chris Millard, “Using Personal Experience in the Academic Medical Humanities: A Genealogy,” Social Theory & Health 18 (December 2020), 184–98.

[30] See, for example Sally R. Munt, introduction to The Ashgate Research Companion to Paranormal Cultures, eds. Olu Jenzen and Sally R. Munt (London and New York: Routledge), 1-2.

[31] Agamben, 75.

[32] White, 3.

[33] W. G. Sebald, The Rings of Saturn, trans. Michael Hulse (London: Vintage, 1998), 70.

[34] T. S. Eliot, ‘Little Gidding’, Four Quartets (San Diego: Harcourt, 1943).

[35] Joyce Appleby, Lynn Hunt, and Margaret Jacob, Telling the Truth About History (New York: Norton, 1994), 259.

[36] Christopher Josiffe, Gef! The Strange Tale of an Extra-Special Talking Mongoose (London: Strange Attractor Press, 2017), 47.

[37] Josiffe, 47.

[38] See www.portalsoflondon.com.

[39] Edward Soja, Thirsdpace: Journeys to Los Angeles and Other Real-and-Imagined Places (Malden: Blackwell, 2014), 20.

[40] Augé, 29-30.

[41] Roger Luckhurst, Corridors: Passages of Modernity (Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 2019); Esme Partridge, “Witchcraft isn’t Subversive,” UnHerd. 15 February 2022.

[42] Augé, 79.

[43] Augé, 30.

[44] Augé, 31.

[45] www.portalsoflondon.com.

[46] William Irwin Thompson, Coming into Being (New York: St Martin’s Griffin, 1998), 200.

[47] London, Archives in Britain of the Societas Iesu, 39.3.3.: ‘Notes on N. B.’

[48] Agamben, 53.

References

Agamben, Giorgio. Infancy and History: On the Destruction of Experience. Translated by Liz Heron. London and New York: Verso, 1993.

Appleby, Joyce, Lynn Hunt, and Margaret Jacob. Telling the Truth About History. New York: Norton, 1994.

Augé, Marc. Non-Spaces: An Introduction to Supermodernity. Translated by John Howe. London and New York: Verso, 2008.

Bloch, Marc. The Historian’s Craft. Translated by Peter Putnam. Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1992 (first published in English 1953).

Bown, Nicola, Carolyn Burdett, and Pamela Thurschwell. Introduction. In The Victorian Supernatural, edited by Nicola Bown, Carolyn Burdett, and Pamela Thurschwell, 1–22. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2004.

Connor, Steven. Afterword. In The Victorian Supernatural, edited by Nicola Bown, Carolyn Burdett, and Pamela Thurschwell, 258–77. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2004.

Darnton, Robert. The Great Cat Massacre and Other Episodes in French History. New York: Basic Books, 1984.

Davies, Owen. Grimoires: A History of Magic Books. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2009.

Derrida, Jacques. Spectres de Marx: l’état de la dette, le travail du deuil et la nouvelle Internationale. Paris: Editions Galilée, 1993.

Eshun, Kodwo. More Brilliant than the Sun: Adventures in Sonic Fiction. London: Quartet Books, 1998.

Fisher, Mark. The Weird and the Eerie. London: Repeater, 2016.

Hodgkin, Katharine. “Historians and Witches.” History Workshop Journal 45 (1998): 271–77.

Huizinga, Johan. Herfsttij der middeleeuwen. Studie over levens- en gedachtenvormen der veertiende en vijftiende eeuw in Frankrijk en de Nederlanden. Leiden: Leiden University Press, 2019. First published in 1919 by H. D. Tjeenk Willink, Haarlem.

Josephson Storm, Jason Ã. The Myth of Disenchantment: Magic, Modernity, and the Birth of the Human Sciences. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 2017.

Josiffe, Christopher. Gef! The Strange Tale of an Extra-Special Talking Mongoose. London: Strange Attractor Press, 2017.

Luckhurst, Roger. Corridors: Passages of Modernity. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 2019.

Millard, Chris. “Using Personal Experience in the Academic Medical Humanities: a Genealogy.” Social Theory & Health 18 (2020): 184–98.

Munt, Sally R. Introduction. In The Ashgate Research Companion to Paranormal Cultures, edited by Olu Jenzen and Sally R. Munt, 1–38. London and New York: Routledge, 2013.

Partridge, Esme. “Witchcraft isn’t Subversive.’ UnHerd. 15 February 2022. https://unherd.com/2022/02/witchcraft-isnt-subversive/

Sebald, W. G. The Rings of Saturn. Translated by Michael Hulse. London: Vintage, 1998.

Soja, Edward. Thirdspace: Journeys to Los Angeles and Other Real-and-Imagined Places. Malden: Blackwell, 2014.

Spengler, Oswald. Der Untergang des Abendlandes. 2 vols. Munich: Oskar Beck, 1918–1922.

Thompson, William Irwin. Coming into Being. New York: St Martin’s Griffin, 1998.

Tsing, Anna Lowenhaupt. In the Realm of the Diamond Queen: Marginality in an Out-of-Way Place. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1994.

Venkadesh, Sudhir Alladi. Off the Books: The Underground Economy of the Urban Poor. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2006.

White, Hayden. Metahistory: the Historical Imagination in Nineteenth-Century Europe. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1973.

Kristof Smeyers is a postdoctoral researcher at the Ruusbroec Institute, University of Antwerp. His work explores the cultural history of mysticism, folklore, the supernatural and the body. He is also interested in non-human histories, and writes about ravens, wolves and jellyfish.